Three Hare Song

by Nathan Steward

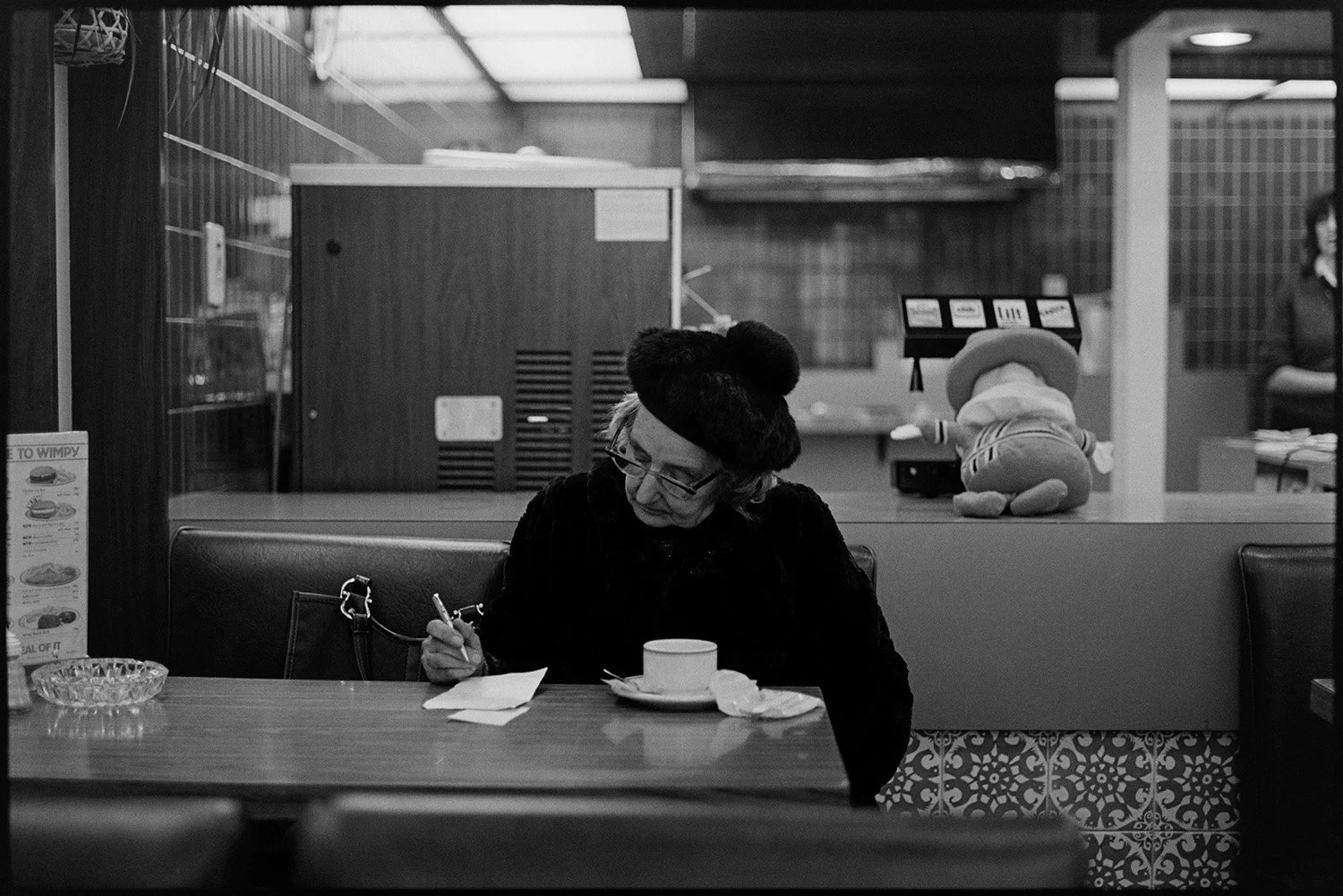

Image credit: Sue Andrew

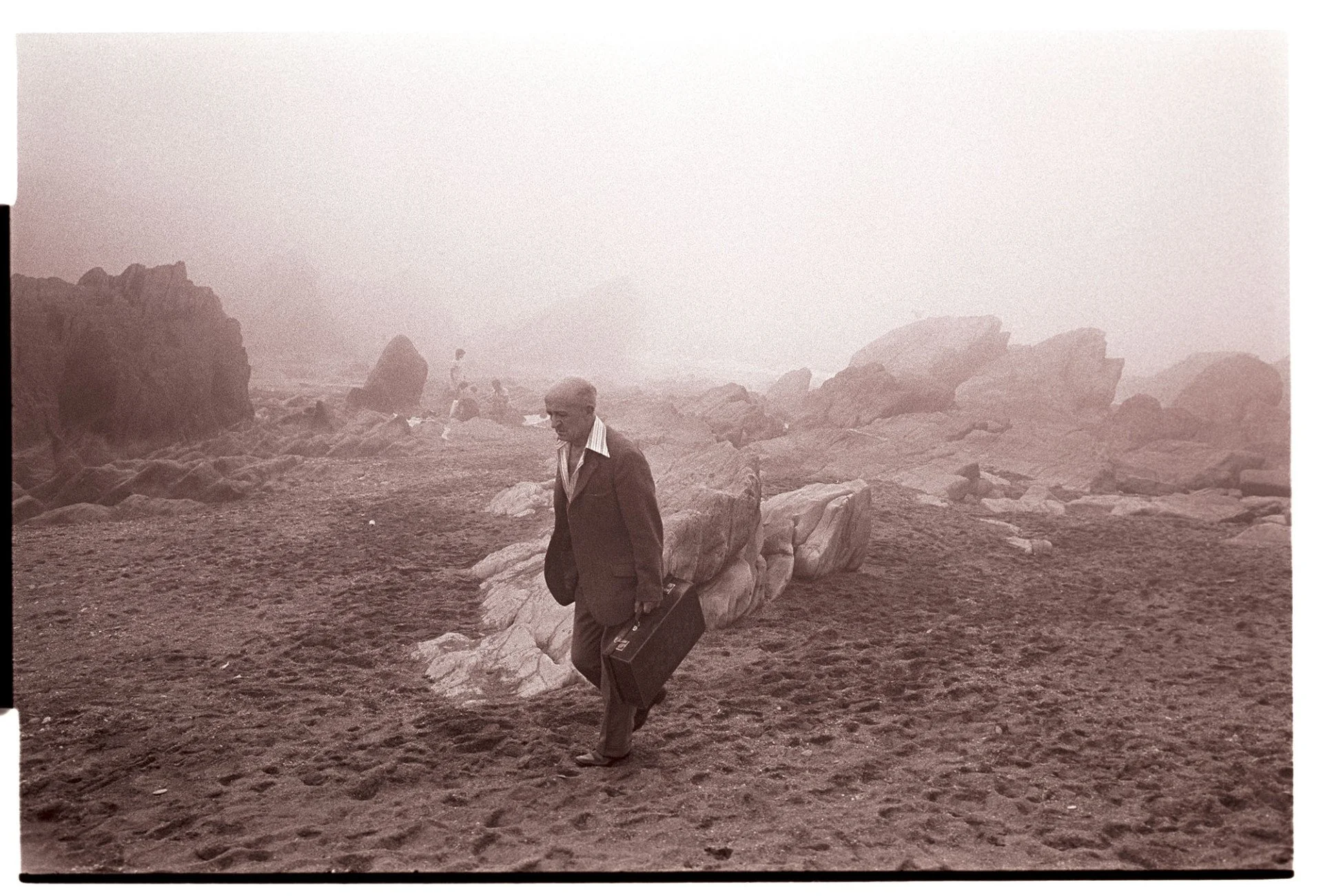

All other colour images by Nathan Steward

Introduction

In the Summer of 2025, I sent out an application for a Devon creative bursary, with a detailed plan for a ‘long-form unique poem of my own design’. It was ambitious and thorough and seemed to possess all the possible answers to any barrier I might encounter – this was, of course, not the case. Kernels of my finished piece can be traced to those early ideas, but even more than what was newly included, is the extent to which I restrained my loftier aspirations. The poem which emerged is tighter, more focused, and yet somehow far longer than initially imagined!

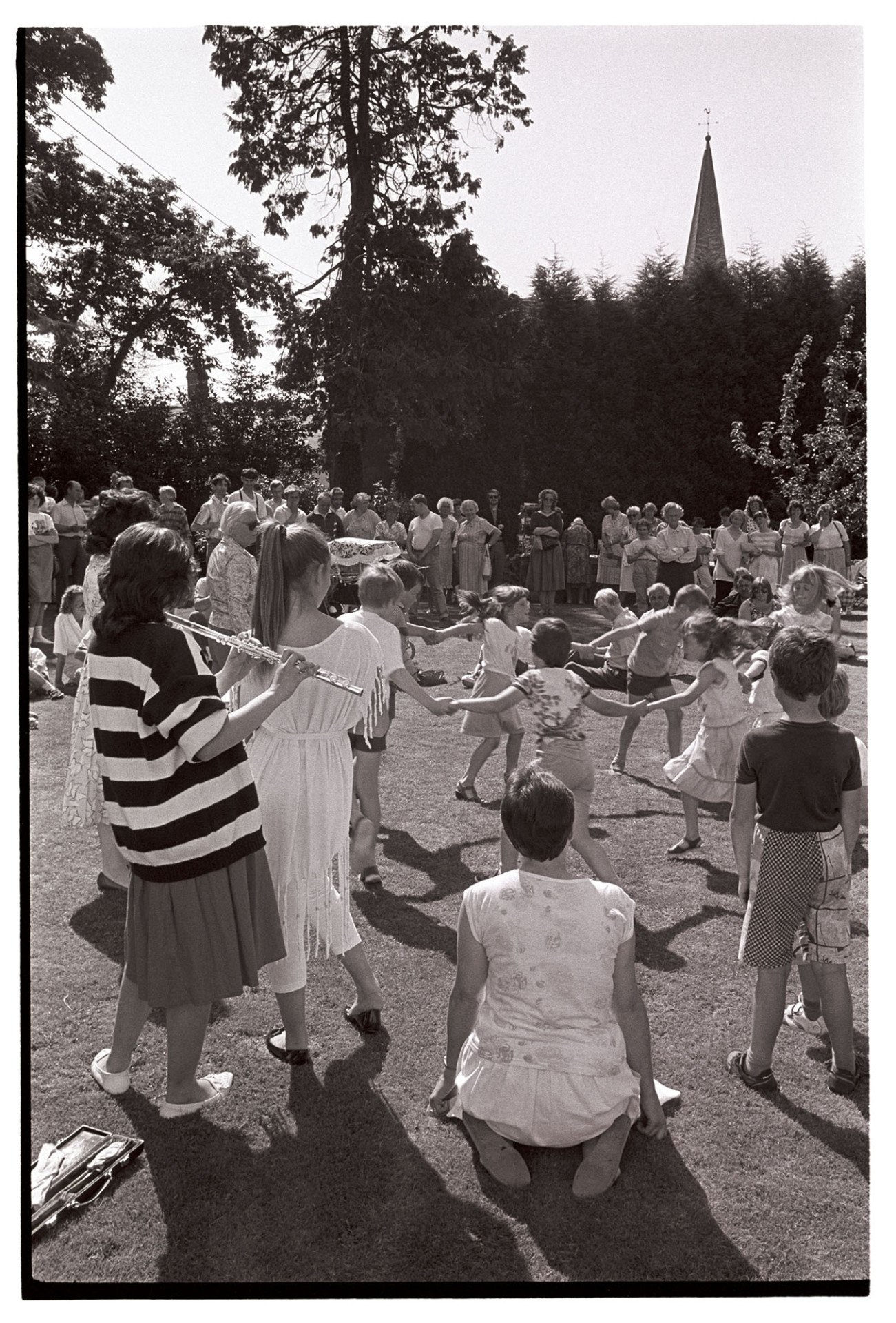

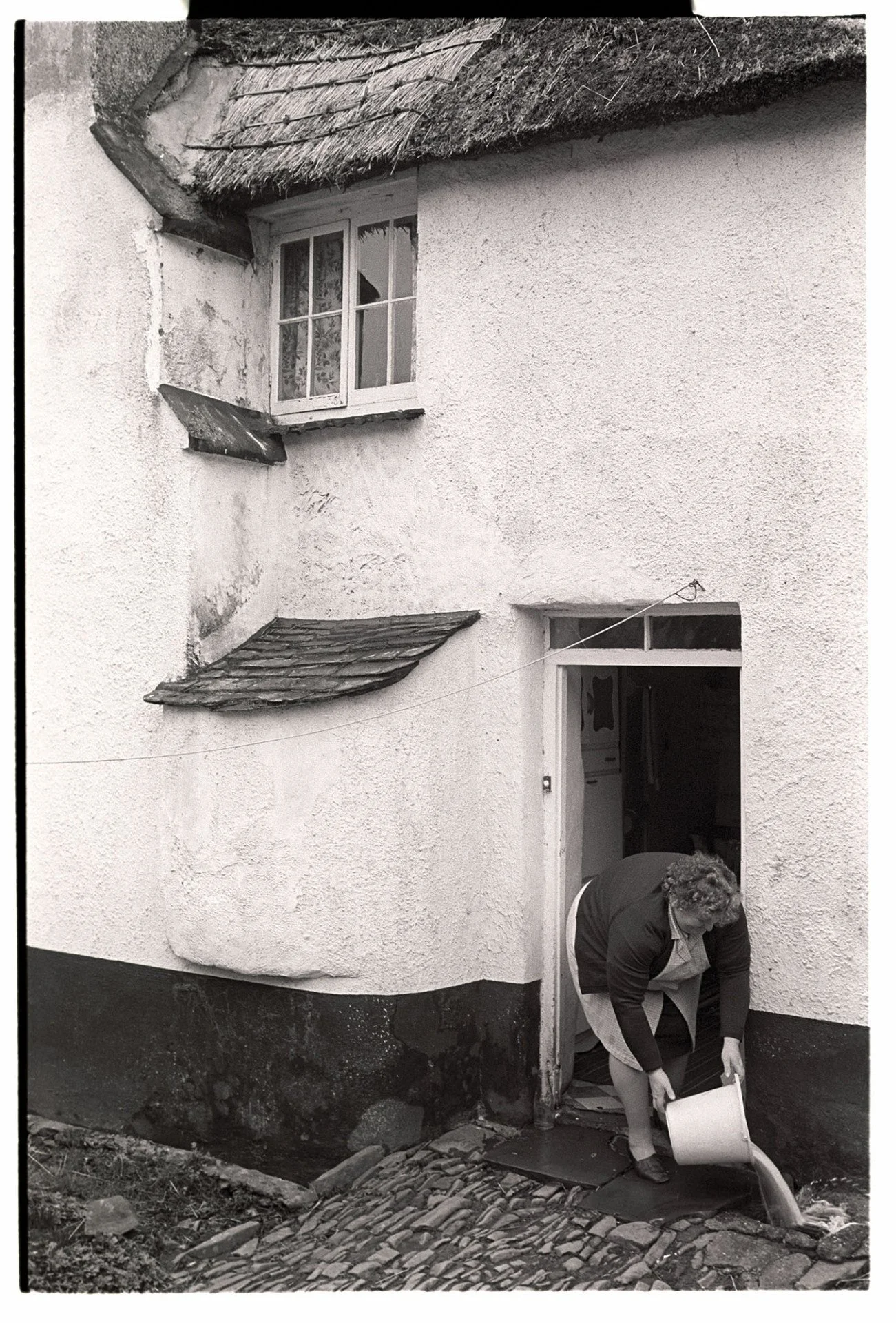

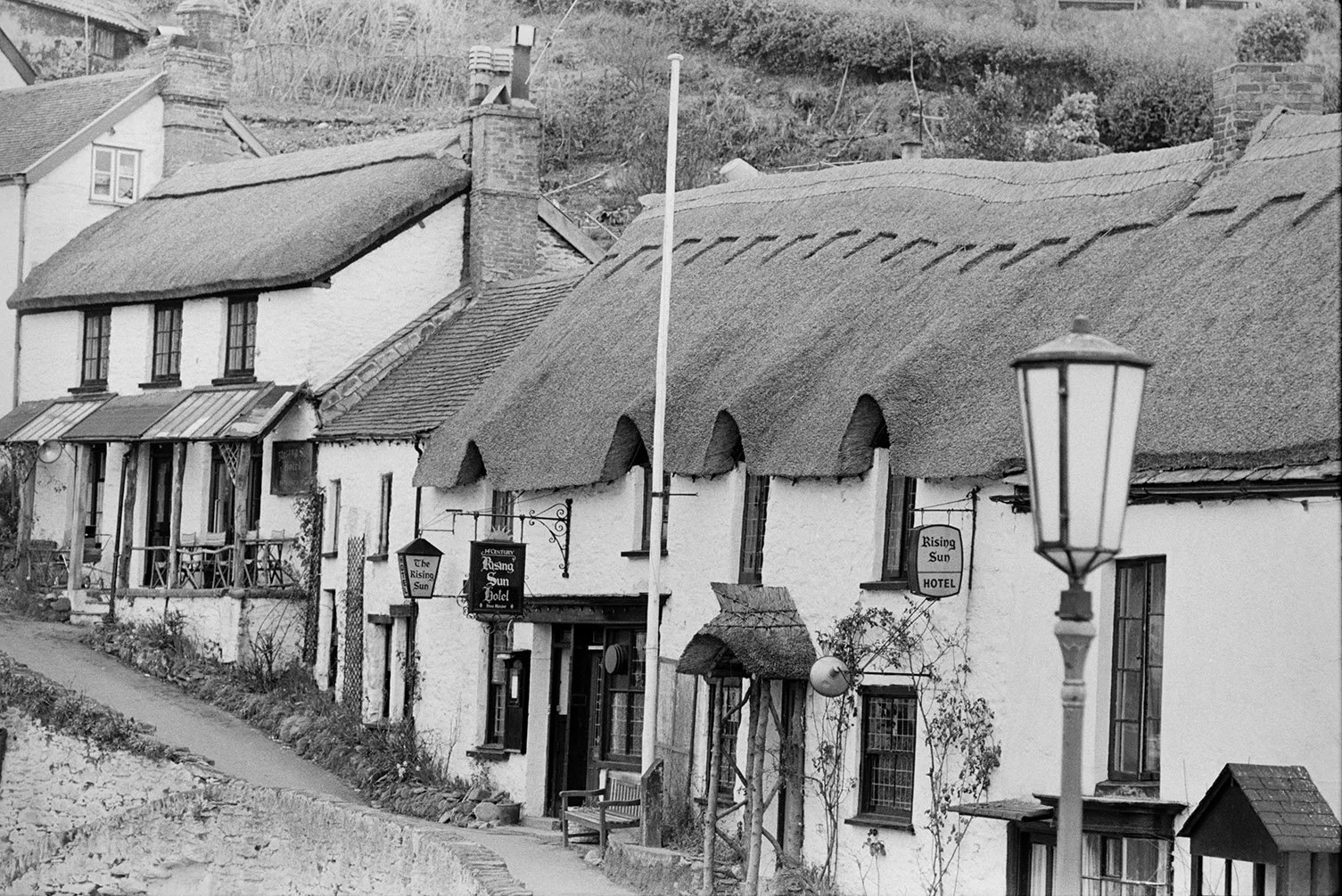

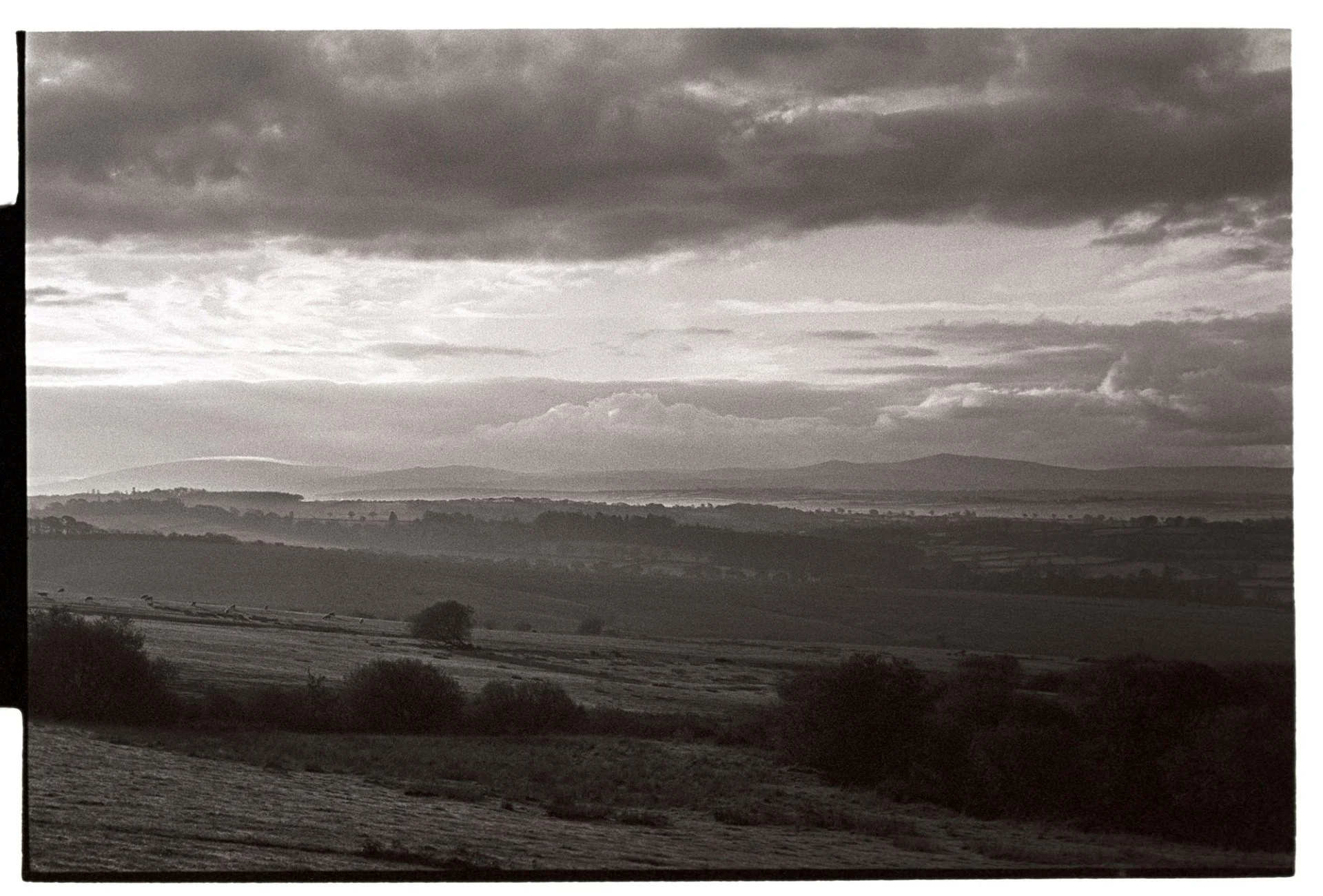

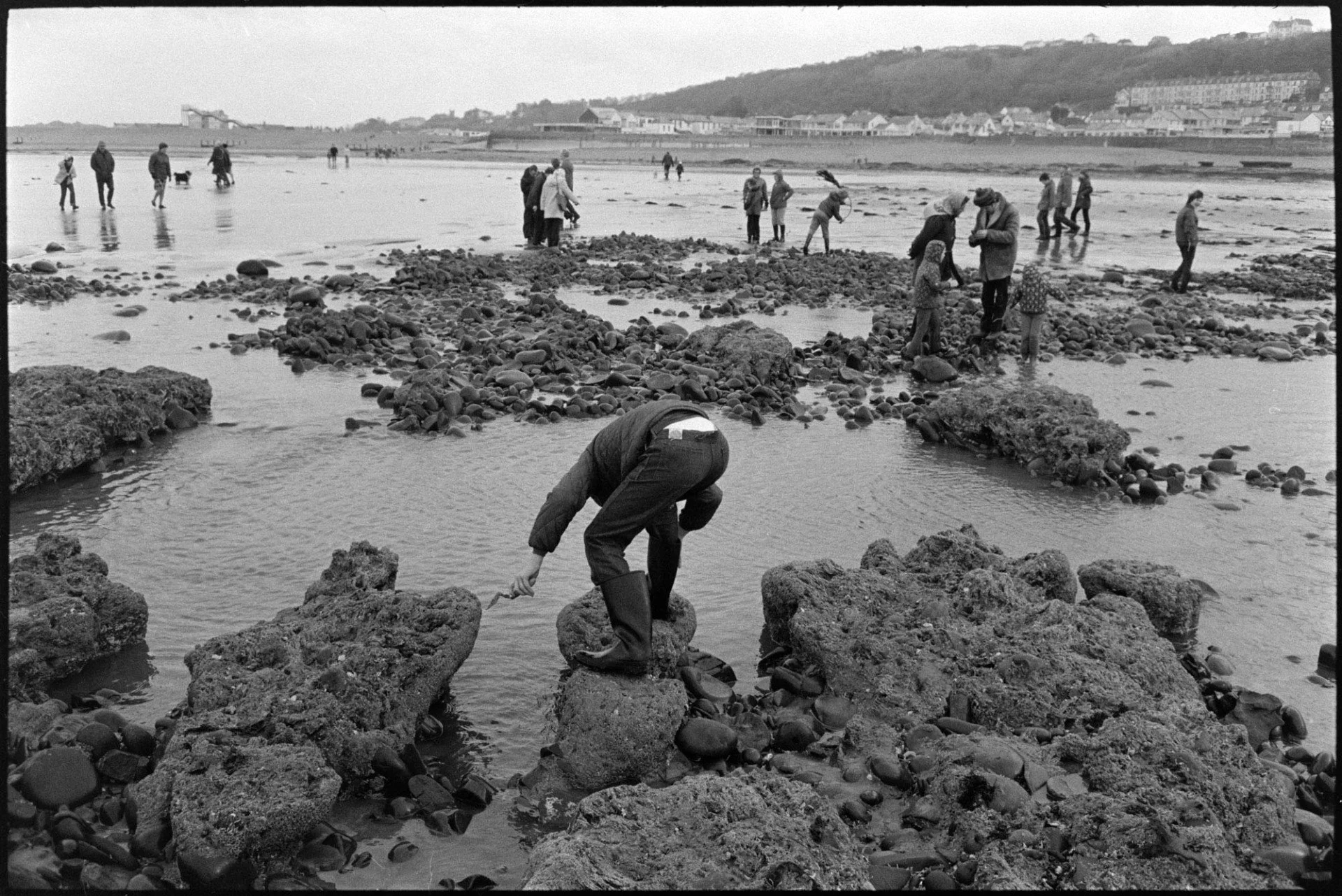

It has been a wonderful experience of walking beaches, cliffs, bogs and moorland – pacing the cobbles where an author’s feet once walked – or even, in the case of Dickens, drinking and leering at patrons in the same pubs they once frequented. The most inspiring aspect of this exploration – and that which links and binds every canto of my piece – is the Exeter Cathedral's Exeter Book. This is the largest (and perhaps oldest) collection of old Anglo-Saxon poetry that we possess; it takes no great leap to brand the text as foundational for all English literature. Throughout my poem, each section begins with an excerpt from the various translated elegies and riddles contained within. These epigraphs reflect the themes of the places and authors explored in each canto and serve to reveal how this seminal, ancient text speaks to all of Devon as well as every author who has ever called it home.

Alongside the Exeter Book is my titular motif for the piece: the Three Hares. A widespread and mysterious symbol, the icon of three interlinked running hares has been discovered in places of prominence for Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism and Islam. It is a metaphor and a riddle and a conundrum – we can track its history and migration, but we still don’t know what it means. Presented both negatively and positively, the Three Hares are often seen as emblematic of rebirth, fertility, lunar cycles, the trinity, or perhaps a mathematical puzzle. What was particularly fascinating to me, is the symbol’s significant concentration in Devon and Dartmoor as opposed to the rest of the country. Rather than cast my own definitions and theories for the hares, however, I decided to embrace this mystery. They are both chained and free – linear and cyclical – rebirth and death, and everything in between. For every story and poem written and performed in Devon, I imagined three hares watching and waiting, always together, always running.

I cannot avoid the fact this is a long poem. So, settle in somewhere wrapped and warm and quiet, perhaps put your phone in a harmless and productive place – like a locked safe or a bin – and relax. I cannot promise great sights or scenes or wonderful smells or tastes in my piece – it is only words – but there is a song hidden in there somewhere, if you listen out for it

- Nathan