Abstract

50 years ago, James Ravilious took up the post of resident photographer at the Beaford Centre, founded in North Devon in 1966 by the Trustees of Dartington Hall. From 1972 until his death in 1999 Ravilious worked as a documentary photographer rooted in rural North Devon. He created a unique picture of Life and Landscape in the small local communities around him and contributed more than 75,000 photographs to the Beaford Archive. Today he is viewed as a rural documentary photographer of major significance.

After considering briefly the Association’s past interest in photography, this paper recalls the creation of the Beaford Centre and its Archive. It then highlights the lasting legacy that James Ravilious has left us through his photographs. Finally, readers are given the opportunity to reflect on their own responses to a sample of his images.

Introduction

Given that our Association’s aims embrace the advancement of Science and Arts alongside Literature it is to be expected that there has been a long-standing interest in photography among its membership. Reaching back 126 years to 1896, we find that among the papers presented to members attending the 35th Annual Meeting, held in Ashburton during the Presidency of the Rev. Sabine Baring-Gould, was one entitled ‘A Photographic Survey of Devon’.

Presented by C. E. Robinson, a Bristol water engineer, this paper referred to a report prepared two years previously by the Congress of Archaeological Societies proposing that systematic photographic surveys be undertaken. Robinson suggested that the Association was well placed to initiate such a photographic survey for Devon. He recognised that this would involve historians, geologists, antiquarians and naturalists working alongside amateur photographers and he drew attention to the value of publishing a selection of the survey’s photographs. He identified thirty types of ‘objects of interest’ that might be covered in such a survey. Along with some obvious choices such as ‘churches’, ‘castles’ and ‘old houses’, he included ‘very old people’ and natural features such as ‘celebrated trees’ and ‘effects of lightning’. Robinson also identified the need to deposit duplicate copies of survey photographs in the Barnstaple Athenaeum and the museums at Exeter, Torquay and Plymouth. (Robinson, 1896)

By the time of Robinson’s paper, the potential of photography was already well recognised. Its development had been gaining growing attention in the Westcountry during the second half of the nineteenth century. In 1855 over 500 people had attended the second annual gathering of the Devon and Cornwall Photographic Society and two years later the Devon and Exeter Photographic Society had been founded. (Kember et al., 2016, 44) Photography was identified as an ‘independent art’ in its own right during the London International Exhibition of 1862 (the same year that our Association was founded). (Anon, 2016)

A recent study of the early days of photography on Dartmoor lists nineteen individual photographers active between 1860 and 1880. (Greeves, 2015) The advent of tourism in the Victorian period was one of the drivers behind the popularity of photography in Devon, with Torquay’s rise as a seaside resort providing one particular stimulus. (Greeves, 2012) Among the most active early commercial photographers in Devon was Exeter-born William Spreat, who by 1862 was offering ‘tourists and visitors’ a choice of more than 300 ‘First-Class Photographs and Stereographs of the principal objects of interest in the counties of Devon and Cornwall’. (Greeves, 2018)

So, conditions in 1896 would have been favourable for the Association to take up Robinson’s suggestion that it organise a county-wide photographic survey, not least because Robert Burnard, one of its most active members and also a council member of the Devon and Cornwall Camera Club, had recently shown a way forward by publishing his four-volume series, Dartmoor Pictorial Records. (Burnard, 1890–4) However, although the Association promptly set up a committee to progress the survey idea and a series of that committee’s reports appeared in the next few annual Transactions, enthusiasm seems to have soon dried up. The committee reported a disappointingly small number of photographs being submitted to it.1

120 years after Robinson presented his paper to its 1896 Annual Meeting, the Association again had photography as a theme for discussion when Dr Tom Greeves chose it as the topic for his 2016 President’s Symposium on ‘Science meets Art – Aspects of 175 Years of Photography in Devon’. (Hurley, 2016) A capacity audience of 130 people gathered at Tiverton to hear an excellent array of presentations on the history of photography in Devon and on its contemporary practice in the county.2 Enthusiasm was again aroused within the Association to become more actively engaged with photography - this time with the idea of setting up a new Photography Section. But again, as with the Association’s response to Robinson’s 1896 paper, interest did not gain sufficient traction to see that suggestion become a reality.

One conclusion that the Association’s 2016 President’s Symposium did demonstrate was that photography was very much alive in Devon and that the county had become home to photographers of national and international significance. Among this number must be ranked the documentary photographer James Ravilious (1939–1999).3

Ravilious started his career as a photographer in Devon in 1972 when he took up the post of resident photographer at the Beaford Centre. He remained living and working in North Devon until his death in 1999. As 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the arrival of this master photographer in our county, it seems timely to review his achievements and celebrate his lasting legacy in this paper presented to the Association’s 160th Annual Meeting, held in Bideford in September 2022. The story begins with the creation of the Beaford Centre in 1966.

The foundation of the Beaford Centre

4

The decision of the Trustees of Dartington Hall near Totnes in South Devon to establish a rural arts centre in 1966 in the isolated North Devon village of Beaford (parish population less than 300) was truly pioneering for its time. To quote one contemporary report: ‘Exceptional (and some would say mad) was the Trustees’ decision to open an arts centre at Beaford … This seemed extravagant and unnecessary.’

It is difficult to appreciate just how remote and often overlooked the scattered small communities of North Devon were sixty years ago. The ‘land between the two rivers’ (the Torridge and the Taw) was still unknown territory to many Devonians. Tourists had not yet come to know the area as ‘Tarka Country’ or flock to walk and cycle on its very popular Tarka Trail. The recognition of the special character of the North Devon countryside by its incorporation into the UNESCO North Devon Biosphere Reserve was still forty years in the future.5

Rural depopulation was a live issue for North Devon sixty years ago. In the late 1950s the Dartington Hall Trustees had funded a sociological study of one particular North Devon parish to examine local population trends. (Williams, 1963) They followed this interest up with a decision to support two innovative projects aimed at addressing social deprivation and the lack of employment opportunities in North Devon. The creation of a rural arts centre at Beaford was one of these and the other was the construction of the £0.25m Dartington Glass Factory which was opened at Great Torrington in June 1967. Eskil Vilhemsson and fifteen other glass blowers were recruited from Scandinavia to train local people in new skills at this factory, a business which is still going strong today under the name, Dartington Crystal. (Derounian et al., 1988, 102)

The concept of the new Beaford Centre (later to be known as the Beaford Arts Centre) had at its heart the ambition “to enrich community life through the public performances of live events’. From its opening day, 20th August 1966, the Centre hit the ground running. An inaugural rural arts festival, ‘Beaford Entertainment’, attracted enthusiastic local audiences to 33 events during September 1966 with the words and music of well-known artists such as Gilbert and Sullivan, Benjamin Britten, Sophocles, and Harold Pinter being performed alongside community events such as bell-ringing and dancing. Soon residents of North Devon were seeing a wealth of professional performers arriving on their doorsteps, including dancers from the Royal Ballet, poets such as Stevie Smith and musicians such as Ravi Shankar and the folk group, Pentangle.

The Centre’s expanding programme was enthusiastically supported by the Dartington Hall Trustees. An initial budget for 1966/1967 of under £2,000 (including £150 from the South Western Arts Association, the regional forerunner of Arts Council England) was soon enhanced by the Trustees ear-marking an operating grant of £10,000 p a. In addition, they invested £38,000 capital funding to acquire Greenwarren House, the village’s former rectory, and convert it into Beaford’s centre for residential courses. (Over the following decades residential courses at Beaford were to provide inspiring and memorable experiences to thousands upon thousands of schoolchildren from Devon and beyond).

By 1968 the Centre’s events programme could include the noted poets, John Fairfax, Ted Hughes and John Moat, hosting a residential poetry course for teenagers, drawing inspiration from the ‘exhilaration of solitude’ that the remote Beaford location offered.6 Links with the British Film Institute brought an ‘International Cinema’ season of twelve films to North Devon and the Trustees went on to take the bold step of establishing the Orchard Theatre in 1969 as the Centre’s very own touring company. By that year Beaford could proudly claim to have promoted some 300 events seen by some 36,000 people in its first three years.

The successful launch of the Beaford Centre benefited greatly from Dartington Hall’s national, indeed international reputation as an innovative arts organisation. (Cox, 2005) But just as significant was the Trustees’ decision to appoint John Lane as the Centre’s first Director. A painter and writer by background, Lane moved to Beaford from a lecturing job at Bretton Hall College of Education in Yorkshire. His visionary zeal lay at the heart of the Centre’s early success. Two particular ambitions drove his approach. First was his insistence on providing high quality arts experiences – ‘excellent professional events to provide stimulus’. The people of North Devon did not deserve anything less. Equally important was his commitment to involve local people in creating programmes that drew inspiration from the special character of the area ‘so that they felt the Centre’s activities were not only [made] for them but by them’.

Lane saw the potential for breaking down barriers between art forms and taking arts activity to communities where nothing of its kind had been seen before. He felt sure that the value of arts to society was underestimated and recognised its power for giving people the chance to participate in life-enhancing experiences. (One of his reports was entitled ‘The Great Art of Cheering Us All Up’).

Beaford’s early years met with keen local interest. The Centre was able to record that in 1971, with the help of an allocation of £18,600 from the Dartington Hall Trustees, 28,907 people had paid to attend 280 events spread across more than 50 communities. with a further 6,000 attending un-ticketed events. By 1972 the reputation of the Beaford Arts Centre was such that the government’s Arts Minister was making his way to North Devon and Beaford was being held up as an exemplar arts centre in a House of Lords debate on regional arts development. At that time it was claimed to be one of only six such professionally run centres in the country.

In a paper to the Town and Country Planning Association’s 1972 national conference John Lane presented an overview of the Centre’s progress to date. (Lane, 1972) He highlighted the five main areas of the Centre’s activities as: music, poetry, exhibitions and entertainment; touring plays; youth and community work; day and evening courses; and short-term residential courses. He also made passing mention of involvement in photography and film-making, referring to plans for ‘photographers (to record the area) and … a small itinerant film crew to make films about North Devon’. Thus, the seeds had been sown for a new venture that would see photography take root in the Centre’s future programmes.

The creation of the Beaford Archive

7

If, from the vantage point of fifty-six years on, the Dartington Hall Trustees’ decision back in 1966 to establish a rural arts centre in a small North Devon village seems remarkable, the idea that an arts centre should seek to establish a photographic archive surely seems even more surprising. This did however fit very well with John Lane’s commitment to community engagement. To him the word ‘Centre’ was something of a misnomer. He was committed to breaking down the well-guarded barriers between arts and community involvement. To him ‘The whole intention is … rather than to have a single arty-ficial oasis, to flood the area with experiences and opportunities’.

The first small steps in establishing the photographic archive at Beaford lay in Lane’s appointment of a resident photographer in 1971. A contemporary Beaford report setting out the scope of this initiative merits quoting in some detail:

‘The origins of a photographer attached to the Centre and permanently working in the community is to be found in the dissatisfaction felt by the Centre for the traditional kind of art exhibition in the rarefied atmosphere of galleries. …. Exhibitions of paintings and sculpture are largely irrelevant to the majority [of people]. … Photography belongs to the spirit of our times’.

The report continued:

[The photographer’s] ‘brief is to photograph life in North Devon in all its aspects, and provide a comprehensive record of a remote rural area and to present this region with an image of itself. … When people ask fifty years from now: “What was life in rural England really like in grandfather’s day?” [these] photographs should provide one kind of answer’.

It set out five ‘initial projects’:

1. ‘Study of Mill Farm, Beaford, through the days and seasons.

2. a photographic study of the village of Dolton, an isolated community above the river Torridge, in the heart of the North Devon countryside. The subjects will be:

(a) The architectural features of the village.

(b) The various village industries and trades (Genette, the fly factory, the fishmonger, the coalman, the butcher who kills his own meat etc).

(c) The children of the village school throughout the day.

(d) The village recreations from football to the carnival.

(e) A number of individuals representing a cross section of the community, showing them at work and in their leisure hours.

3. A project with the social historian, E W Martin, … to photograph and interview old people in the area who can talk about life as they knew it in Devon 60 or 70 years ago. …

4. A series of photographs illustrating the various rural recreations in North Devon: otter and fox hunting, pigeon and game shooting, village cricket, football, badminton, and fishing, bell-ringing, darts matches, Women’s Institutes, Carnivals, dances, bingo, the cinema, whist drives and drinking in the pub.

5. A study of a complete form of school leavers from Torrington County Secondary School who … can speak for their contemporaries. …’

The report concluded:

‘When this study is complete, the Beaford Centre will mount an exhibition of photographs in the village hall, accompanied by taped interviews, old photographs and a brief description and social history of the village’.

It seems clear from this 1971 report that the impetus for this initiative lay very much in seeing photography as a medium for creating an historical and social record rather than recognising its value as an art form. This makes it seem even more remarkable that an arts centre should have embarked on establishing an archive at a time when major museums had been coming late to giving photography the attention it deserved. (Anon, 2016)

For the Centre’s first resident photographer, John Lane appointed Roger Deakins, who came to Beaford from the Bath Academy of Art where he had been studying Visual Communications. Torquay-born and the grandson of a Devon farmer, Deakins was initially employed for six months from September 1971 to April 1972 at £15 per week (plus expenses) with the help of a £150 grant from the South Western Arts Association. The Centre was keen however to extend his employment, explaining ‘Unless a grant can be found to extend his work for a further 6 months… a unique record of English life [will be] left incomplete.’

Roger Deakins’ personal interests lay in film as well as photography and before 1972 was out he had left Beaford to attend the National Film School. He went on to a highly successful Oscar-winning international career as a cinematographer. During his time as Beaford’s first resident photographer, he made a significant impact. He created an initial portfolio of over six thousand black and white photographs of life and landscape in North Devon and showed the benefits to be had from embedding a documentary photographer in a rural setting. His distinctive North Devon images, a selection of which has recently been published, formed the foundation of what has become known as the Beaford ‘New Archive’. (Deakins, 2021) We cannot know what might have happened for photography – and film – at Beaford had Deakins stayed longer but his decision to move on opened the way for John Lane to appoint James Ravilious in his place.

James Ravilious and the Beaford Archive 1972 to 1989

8

Serendipity played a leading role in James Ravilious’s appointment as the Beaford Centre’s full-time resident photographer in 1972. That year he and Robin, his wife, had had to leave their London flat as it was being demolished in advance of urban redevelopment. They chose to move to Devon where Robin had been given a small cottage on an estate that had long been in her family’s ownership. That cottage happened to be in the North Devon parish of Dolton, the same Dolton that had been identified as the subject for the Centre’s first village photographic survey. Dolton lay close to Beaford and the Raviliouses’ move to Devon came in the same year that Roger Deakins left his post as Beaford’s first resident photographer.

In London Ravilious had been working as an art tutor at Hammersmith College of Further Education so, on moving to Dolton, he approached John Lane about the possibility of teaching some drawing or wood engraving classes at the Beaford Centre. When Lane suggested that he might take some photographs for the Centre there was no looking back. Ravilious had little practical experience of photography but he had been deeply inspired by the exhibition of the work of the French photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, that the Victoria & Albert Museum had put on in London in 1969.9 He was later to write:

‘It was the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson which opened my eyes to the potential of the photograph as a serious, and in his hands, profound comment on life. Under his influence I try always to take an honest picture, neither setting up the subject beforehand nor doctoring the print afterwards.’

Ravilious was a person of immense kindness, integrity and modesty. He overflowed with both creativity and enthusiasm and he was ever ready to share these precious gifts with others. Such was his friendly and unassuming approach to taking photographs that local people soon took him and his work to heart.

Making his way through the countryside (first by scooter, later in a three-wheeled Robin Reliant), he quickly began to build up a superb portfolio of contemporary photographs of life in the communities around him. Through his eyes the ordinariness of everyday life took on extraordinary and sometimes sublime meanings. Working with his trusted Leica camera and almost always in black and white (to him, green was too dominant a colour in the countryside), he developed his self-taught skills to create a body of work of the highest artistic quality. In doing so he set himself exacting standards. From an overall total of more than 75,000 of his photographs that have come to form the heart of the Beaford ‘New Archive’ he was to identify just 401 as being of ‘Best’ quality and only another 1,300 as worthy of being considered ‘Good’.

He also recognised the value of copying early photographs, reaching back to the nineteenth century, held by local families. This idea had been floated by John Lane in 1971 and some work had started in 1973. But it was an invitation to attend a meeting of the Dolton WI in 1975 to judge the ‘Most Interesting Old Photograph’ competition that spurred Ravilious forward on this front. As a result, the Beaford ‘Old Archive’ (as it is known) contains over 9,000 copies of old photographs, loaned by local people.10

Ravilious worked for Beaford for seventeen years, devoting his life to creating an outstanding archive, made up very largely of photographs taken very locally, within a ten-mile radius of the Centre. In the 1970s and 1980s many aspects of local life in rural North Devon seemed on the point of change and he had an eye for picturing not just what was at risk of disappearing but also new ways of living and working. For example, he portrayed the construction of the North Devon Link Road as it cut its swathe across the countryside. He was aware of the significance of his photographs as items of social and historical record. But his wonderful eye for a picture and his quick, quiet response to any situation he came across meant that he was capturing the ‘here and now’ as well as recording the passing of traditional ways of living. This is well demonstrated in his and Robin Ravilious’s In the Heart of the Country, published in 1980. For this book he selected 113 images that he had taken over the previous eight years with Robin writing their captions and an introductory essay. At the time of their publication many of these photographs would have had a ‘present-day’ feel about them but, forty-two years on, they echo with different, distanced resonances.

For many people Ravilious was the Archive during the years he worked for the Beaford Centre but he was aided by others. Robin Ravilious was always at his side, collaborating on projects, co-curating exhibitions and writing commentaries on his photographs for publications. George Tucker worked with him as assistant photographer between 1977 and 1982, developing the Beaford Old Archive by making copies of old photographs dating from between 1870 and 1940.11 Other people, such as local Beaford resident Richard Davin, helped with putting the records of the photographs in order. Cataloguing the collection was further progressed by a team working under the Manpower Services Commission’s temporary employment programme in the second half of the 1980s.

During these years, Ravilious developed a lasting friendship with Chris Chapman, another documentary photographer who had come to make his home in Devon – at Throwleigh on the north-east fringes of Dartmoor. By coincidence Chapman took his first photographs on Dartmoor in 1972, the same year that Ravilious arrived at Beaford. Like Ravilious in North Devon, he became rooted in his local community on Dartmoor. Fifty years on, he is still adding to his inspiring portfolio of photographs and films of life and landscape on and around the moor. (Chapman, 2000) The combination of both Chapman’s and Ravilious’s work represents a pair of complementary archives of rural photography which are surely without parallel in this country.12

John Lane’s original vision for the Beaford Centre not to be an ‘arty-ficial oasis’ but ‘to flood the area with experiences’ was one which Ravilious could very much identify with. He and Robin Ravilious masterminded a series of hugely popular Beaford exhibitions, showcasing his ‘New Archive’ photographs alongside the copied ‘Old Archive’ images that had been loaned by local people. In the 1980s these exhibitions had titles such as Time Off 1858-1950, Eighty Years On (photographs taken between 1900-1980) and Glorious North Devon. The North Devon Show, where as many as 1,600 people would come to see an exhibition, was a successful venue for these exhibitions which then toured around small communities in North Devon.

Ravilious’s photographs were also being exhibited outside Devon. As early as 1973 he was showing his work at the Museum of English Rural Life (Reading) and later venues included the Serpentine Gallery (London), the Photographers Gallery (London) and The Octagon, the Royal Photographic Society’s gallery in Bath. (Batten, 1989) Touring exhibitions included his series of orchard photographs taken during a very fruitful commission for the ‘Save Our Orchards’ campaign run by the environmental charity, Common Ground. (Common Ground, 2000)

Ravilious was allowed considerable freedom at Beaford to pursue his work. This gave him the flexibility to respond to opportunities as they unfolded around him but working relationships between him and the Centre could present challenges. John Lane had left the post of Centre Director shortly after Ravilious’s arrival and, although he continued to be involved as Chairman of its Council of Management over the period 1973-87, subsequent Centre Directors would not always give the Archive the priority it deserved.13 In the mid-1980s the suggestion was even made that all new photography for the Archive should be ceased and instead a writer in residence should be appointed to draw her/his inspiration from the photographs already in the Archive.

Funding was a recurring issue. Although the Centre’s overall budget grew significantly over the years, Ravilious was often working on a shoestring and he devoted many more hours to the Archive than he was contracted for. The Centre lacked a dedicated room for the Archive and he had to create his own darkroom, first in his cottage at Dolton and then in the house in the larger village of Chulmleigh where he and his family moved in 1987. A funding crisis at the Centre in 1980 had led to his appointment being reduced to a part-time one and eventually, in 1989, his role as the Beaford Centre’s resident photographer was brought to an end.

The legacy of James Ravilious’s photographs

It is to Devon’s great good fortune that Ravilious chose to live, for all twenty-seven of his working years as a photographer, in the same area of North Devon, among small communities that he came to know so well. After leaving his job at Beaford he spent the last ten years of his life working on a freelance basis, taking on specific commissions and contributing to various publications and exhibitions. He selected 197 of his photographs for his own book, A Corner of England, which was published in 1995, fifteen years after his first collection had appeared in The Heart of the Country. (Ravilious, 1995) His standing as a master photographer gained the wider recognition it deserved in 1998 when Peter Hamilton, an Oxford academic who recognised the outstanding significance of his work, published An English Eye: The Photographs of James Ravilious. (Hamilton, 1998) This presented 113 of Ravilious’s finest photographs with an appraisal of his standing in the world of documentary photography. So struck was the well-known author, Alan Bennett, by Ravilious’s achievements as a ‘superb exponent of the Englishness of English Art’ that he was moved to write the Foreword to the book – even though he had to confess that ‘Except to pass through on the train I have never been to Devon’! Bennett went on to provide narration for James Ravilious: A World in Photographs, a thirty-minute film by the locally-based filmmaker Anson Hartford, first aired by the BBC in 2007.

The publication of Hamilton’s An English Eye followed on from a major Ravilious retrospective exhibition under the same title that the Royal Photographic Society showed in its Octagon Gallery in Bath in 1997. In the Society’s view Ravilious’s photographs represented " ... a unique body of work, unparalleled, at least in this country, for its scale and quality". The Society confirmed its high opinion by awarding him Honorary Life Membership. The Bath exhibition proved to be a landmark one which went on to tour a range of venues in the following years. Such has been its lasting impact that, in 2021, the Burton at Bideford gallery made the welcome decision to acquire the exhibition’s full set of 135 prints to add its permanent collections. This has secured a lasting home for this superb selection of Ravilious’s photographs in his native North Devon.14 Fittingly, in the same year, the Devon History Society unveiled one of its ‘blue plaques’ in Ravilious’s honour on the front of his family home in Chulmleigh and a new appreciation of his work was published by the Royal Photographic Society. (Wright, 2021)

Ravilious’s legacy as one of the country’s leading rural documentary photographers has been marked in other ways. In the summer before he died, Peter Hamilton, author of An English Eye, recorded a series of conversations with him, and six hours of these recordings are now accessible in the National Sound Archive as part of the Oral History of British Photography project.15 In 2000 the prestigious Leica Gallery in New York City selected some of Ravilious’s finest images to show alongside photographs by another leading documentary photographer, Humphrey Spender, in its The Landscape and People of England exhibition.

2000 also saw the publication of Peter Beacham’s fine Down the Deep Lanes, in which 93 of Ravilious’s photographs illustrated Beacham’s evocative essays on themes such as ‘lane’, ‘field’, ‘corrugated iron’ and ‘weather’. (Beacham, 2000) More recently, in 2017, James Ravilious A Life, a lovely biography written by Robin Ravilious, was published (Ravilious, 2017) as was James Hatt’s large-format personal selection of 78 photographs. (Hatt, 2017)

And what now of the Beaford Archive? Today, fifty-six years after the Dartington Hall Trustees created the Centre and thirty-three years after Ravilious left his job as its resident photographer, Beaford (the current name for the organisation that started life as the Beaford Centre) flourishes. It is now an independent arts charity, recognised as a National Portfolio Organisation by Arts Council England. Much has changed. The Orchard Theatre Company has long since gone and in recent years Beaford’s residential centre, Greenwarren House, has been sold. But those founding ambitions for providing high quality creative experiences and connecting with local communities remain as constant and inspiring as they were back in 1966. Beaford’s ongoing commitment to its unique Archive is such that it identifies it as one of the organisation’s three main programmes (the other two are Education and Events).16

The priority Beaford now gives to the Archive has been well demonstrated by its undertaking, in 2016-19, Hidden Histories, a highly successful £600,000 National Lottery Heritage Fund project to digitise the New Archive and publicise it more widely. The entire Archive collection of over 100,000 images has been cleaned and a new master record created. This features 78,977 of Ravilious’s negatives and a further 6,670 of Roger Deakins’. The project’s scanning of the New Archive images has led to digitised copies being posted for all to see on the Beaford Archive website. This has a fully searchable function for selecting individual images with the added attraction of people being able to purchase digital copies. The lottery project also catalogued the Old Archive images with a view to digitised versions of these being added to the website. In addition, it recorded and transcribed over 125 hours of interviews with local people connected with photographs in the Archive.17 And, following on from the Hidden Histories project, Beaford has published a new book on the North Devon Coast, illustrated with 73 photographs from the Old and New Archives. (Edgcombe, 2021)

Thanks to the continuing commitment of Beaford to the Archive, the photographs of James Ravilious can today be appreciated by an ever-widening audience. The fact that they continue to make such a lasting impression on people is due to a number of factors. Two in particular seem to stand out - the exceptional eye Ravilious possessed for picturing the moment and for composing such superb images; and the deep sense of belonging that he felt through living his life alongside those of the people his photographs reflect. His and Robin Ravilious’s In the Heart of the Country, published in 1980, was fondly dedicated to ‘the people of North Devon’ and on his gravestone in Iddesleigh churchyard James Ravilious is remembered as a ‘photographer who loved this countryside and its people’.

Reflections on 7 photographs

Viewers respond to looking at a photograph in many different ways. So, there is little to be gained through trying to generalise on what a particular image means or seeks to convey. This paper concludes by presenting a small sample of Ravilious’s photographs, accompanied by the author’s personal reflections upon them. Hopefully this will encourage readers to explore their own responses to these images and to the many others that they can discover on the Beaford Archive website and in available publications.18

Fig. 1 Gateposts 1981 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

A Trinity of gateway, tree and church stands silent against a solid sky. To gaze across to St Mary’s Church in the parish of Ashbury, is to take your eye into deepest Devon. This is one of the smallest, remotest of Devon’s 422 parishes (Harris, 2004) – no village centre (population of only 35 in the mid-twentieth century), no ‘big house’ (demolished the 1930s), and no casual passers-by (this is not on the road to anywhere else).

The few visitors who find their way to Ashbury mostly come and go cocooned in the comfort of their cars. But, if you make the journey on foot using public transport, you can garner a far deeper feel for the rhythms of life and the lie of landscape that give this area of Devon countryside its special character. An eighty-minute bus ride from Exeter will take you only as far as Castle Cross where you alight high on the crest of Broadbury, an exposed ridge running across North-West Devon. You then embark on a two-mile wander along quiet Devon lanes. Remembering to turn right at Bogtown, you at last find yourself standing where Ravilious stood in 1981. What inspired him to come this way, you wonder.

Today the gateway has been widened, the tree rises still magnificent against the sky and the church is closed. Officially at least. It no longer features in the Church of England’s listing of its 618 places of worship in Devon (Gilpin and Gilpin, 2008). At the time of Ravilious’s visit farm animals roamed the churchyard and St Mary’s was about to be formally declared redundant. But not unloved. Wonderfully, the door still opens thanks to the church being cared for by a family that holds its ancient roots in Ashbury. Inside you come as close to stillness as you can anywhere in this transitory world. And someone has pinned up on the wall their own poem inspired by once looking at this photograph.

Fig.2 Olive Bennett with her Red Devon Cows, Cupper’s Piece 1979 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

Many of Ravilious’s most striking photographs open our eyes to the close relationship between farmers and the animals in their care. This is one of his best-known and most reproduced images. It featured in the Leica Gallery’s 2000 exhibition in New York City (and, as a result, in the pages of The New Yorker magazine), the Victoria & Albert Museum acquired it for its permanent collections, it helped inspire the BBC’s 2007 film of Ravilious’s work and in 2021 it fronted the Burton’s publicity for its An English Eye exhibition in Bideford. It is a picture that has attracted a range of different responses from viewers.

Olive Bennett and her prize-winning Red Devons used to be a familiar sight to travellers as they crossed Beaford Moor on their way to and from Great Torrington. A detailed 1963 study of rural life in North Devon found that local people referred to four different types of farmers – ‘real farmers’, ‘good young farmers’, ‘dog and stick farmers’ (those who did little work themselves and liked to think they were gentlemen farmers) and ‘Up Country Johnnies’ (people who had moved in from outside the Westcountry). (Williams, 1963, 14) Ravilious always photographed for real and this image reminds us that not all real farmers are men.

Fig.3 Running for the school bus 1982 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

This is an image that never stays still. The boy will always be running despite the nearby road sign’s warning ‘Slow’ and the headstones’ promise of eternal rest. There are reminders here of the maxim attributed to a medieval German theologian: ‘There is no stopping place in this life – nor is there ever one for any person’. To those who know the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson (an inspiring hero for Ravilious), there is a distant echo of his split-second image, taken fifty years earlier, of a be-hatted gentleman striding over a Paris puddle on his way to who knows where. (Clair, 1998, 23)

Ravilious never cropped his photographs and this one demonstrates his fine sense for composition as well as his skill in ‘catching the moment’. He took it from the tower of St Mary’s Church in the North Devon village of Atherington. Health and Safety restrictions have reduced opportunities today to climb the stairs in our medieval church towers. But if you ever get the chance, do take it. You never can be sure what you will see as you look down on our world from above.

Fig.4 The BBC Computer, Primary School Open Day 1985 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

Ravilious had an eye for what was becoming new in village life as well as for old ways that were at risk of disappearing. We so take computers for granted today that it has become hard to appreciate or recall the amazement – and sometimes bafflement – that their arrival in people’s daily lives brought. Here the generations come together as Mrs Agate and Dolton Primary School children tentatively explore the wonders of the modern machine.

As Robin Ravilious has pointed out, there is a nice comparison to be made between this photograph and one of the old Dolton pictures loaned by a local resident for copying into the Beaford ‘Old Archive’. Dating back to the first decade of the twentieth century, that image recorded an inquisitive group of villagers gazing at the first car, a Wolseley, to be owned by a Dolton resident – the local doctor, Dr Alexander Drummond (1856-1908). The first arrival of the car, as later that of the computer, marked a real turning point in rural lives in terms of communication with the ‘outside world’.

Fig.5 Barnstaple Pannier Market 1979 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

Market day has long been the traditional highpoint of the farming week in North Devon. Go back sixty or seventy years and some farming families never travelled further than their local market town except on special occasions. The North Devon towns of Barnstaple, Bideford, Great Torrington and South Molton retain their grand market halls although open-air cattle markets in their town centres have gone.

Barnstaple’s splendid Pannier Market, built in 1855, still plays a key part in the social and commercial life of the town. Fashions – both in people’s clothes and also in the types of food and other goods on sale – have changed since Ravilious took this photograph on a crowded market day forty-three years ago. The author’s mother, growing up during the First World War on her family’s small farm at Swimbridge, retained vivid memories of taking eggs to sell at Barnstaple Pannier Market during that war – and seeing the crowd turn blacker month by month as more families went into mourning for their menfolk lost on the battlefield.

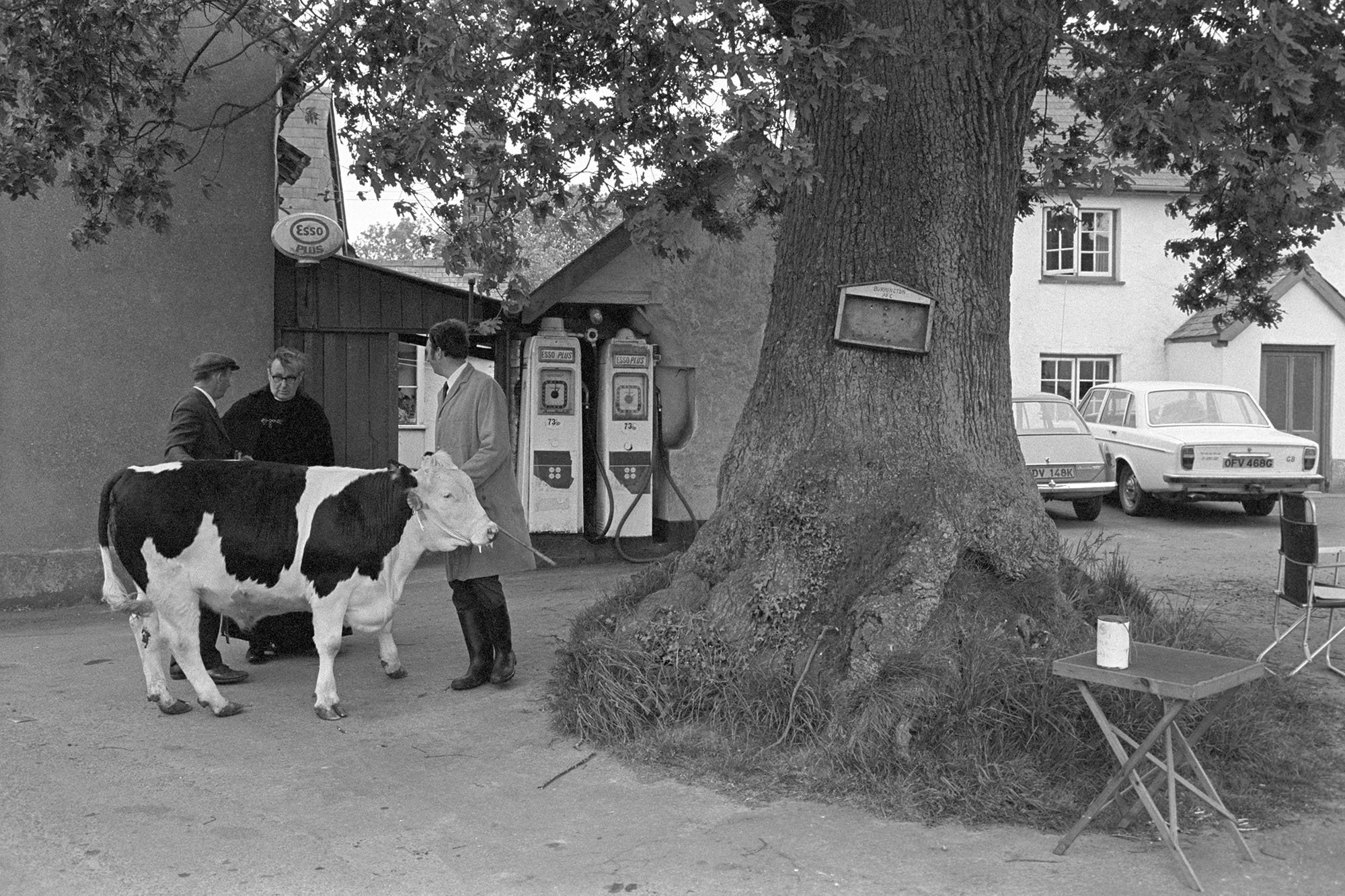

Fig. 6 Reverend Richards and prize bullock beneath the village oak 1975 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

Ravilious never artificially created scenes for his photographs but sometimes one of them can seem so replete with artfully spaced detail that it reminds you of a stage set. Shakespeare’s line that “All the World’s a Stage” could apply to this image very well, with the ‘players’ being the tree, the folding table, the pumps and the cars as well as the parson and the farmers with their prize-winning, rosetted bullock. The ‘village tree’ still remains a prominent feature in the centre of a good number of Devon villages but its function as a community noticeboard has faded. In this photograph the village football team’s noticeboard, neatly aligned to the lean of the Burrington Oak, hangs empty – pending the start of the new season perhaps.

It used to be said that the essentials for a village’s well-being were the five Ps – Primary School, Public Transport, Post Office, Parish Parson and Petrol Pump. (Derounian et al., 1988, 1) Burrington, like so many other North Devon villages, has seen these ‘essentials’ fall away one by one. Its annual Trinity Monday Sheep and Cattle Fair, the event that set the scene for this photograph, came to an end in 1993.

Fig.7 Chawleigh Week Cross 1988. (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

Ravilious had great enthusiasm for ‘laning’ – the art of exploring country lanes and opening your eyes to whatever you happen to encounter. Here he has paused beneath one of Devon’s many thousands of rural signposts. Presiding over its crossroads as a silent sentinel of place, it stands ever ready to guide the wayward traveller and to offer passers-by some sense of certainty.

Its four arms, with their gracefully curving supports, raise questions for the traveller. Who was it who first measured the way to Barnstaple so carefully to be sure that it was eighteen and a quarter miles and not just a plain eighteen (or eighteen and a half)? What obstacles lie in wait for the incautious motorist tempted to take the shorter route to Chulmleigh? And what ever will you find when you get to ‘Sth Molton Rd’?

The image brings to mind a conversation the photographer Chris Chapman had nearly fifty years ago when he was travelling Dartmoor in the company of his donkey, Mistletoe. A local resident, who had worked for forty-eight years as a milkman living deep in the moor near Princetown, told him:

‘One day a chap came ‘ere and said “Ernie, you’ve seen nothing of the world, stuck out ‘ere all your life!” I told him straight, “I’m just like a signpost. I may not be going anywhere but I can tell you a lot about where you’re going!”’ (Chapman, 2000, 127)

Back in the 1980s the local council clearly felt it important to keep Chawleigh Week Cross well-posted. It presents a different, decaying picture to the passer-by in these days of SatNav and Google Maps. (Westcott, 2021)

Notes

1. Robinson’s paper was previously mentioned in the millennial volume of the Association’s Transactions. (Timms, 2000, 143-4) Research by Association members in 2018 identified that it held its own archive of over 150 photographs. See https://devonassoc.org.uk/da-photographic-archive/ (accessed 15/1/22). In 2019, as part of a comprehensive review of its photographic collections reaching back over 160 years, the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter hosted a symposium on Collecting Regions: Photography and a Sense of Place. This drew attention to little-known aspects of the museum’s collections that have been acquired over the years. See https://rammuseum.org.uk/photography-at-ramm-new-discoveries-new-directions/ (accessed 15/1/22).

2. The contemporary Devon-based artist photographers who spoke at the Association’s 2016 symposium were Chris Chapman, Susan Derges, Gary Fabian Millar and Jem Southam. The 2016 symposium also highlighted the extraordinary photographs of Association member, Margaret Tomlinson, (1905-1997), who worked for the National Buildings Record during World War II. Many Devon subjects feature among nearly 3,500 of her photos which English Heritage made available online in 2018 to mark the centenary of women first getting the vote in this country. See https://heritagecalling.com/2017/03/28/a-race-against-destruction-the-wartime-photography-of-margaret-tomlinson/ (accessed 15/1/22).

3. Chris Chapman spoke about the work of James Ravilious, who had also been the subject of a presentation by Robin Ravilious at the Association’s 2013 President’s Symposium on The Inspiration of Devon. See https://devonassoc.org.uk/symposium-2013/ (accessed 15/1/22).

4. Information in this section, including the quoted extracts, is drawn from documents relating to the Beaford Centre 1965-90, deposited in the Devon Heritage Centre (Exeter) under references T/B 1–10. These include a series of Annual Reports, in which the Beaford Archive regularly featured.

5. The North Devon coastline was designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in 1960 but it was not until 2002 that the special character of North Devon’s inland area was recognised by its incorporation into the UNESCO North Devon Biosphere Reserve. Thanks to the far-sighted efforts of Devon County Council, the Tarka Trail, a long-distance walking/cycling path along old North Devon railway lines, was opened in stages during the early 1990s.

6. This 1968 course was the launch-pad for John Moat (1936-2014) and John Fairfax (1930-2009) to found the Arvon Foundation with the aim of ‘providing time and space away from school for young people to write poetry’. In 1972, Totleigh Barton at Sheepwash in North Devon was opened as Arvon’s first residential centre. Ted Hughes (1930-1998), another poet with strong North Devon connections, played a key role in the success of Arvon, which, like Beaford, flourishes to this day. See https://www.arvon.org/about/history/ (accessed 15/1/22).

7. Information in this section, including the quoted extracts, is drawn from documents relating to the Beaford Centre 1965-90, deposited in the Devon Heritage Centre (Exeter) under references T/B 1–10. These include a series of Annual Reports, in which the Beaford Archive regularly featured.

8. This section draws on Robin Ravilious’s wonderful biography of her husband (Ravilious, 2017). Other biographical detail can be found on the website www.jamesravilious.com which includes listings of publications and the principal exhibitions of his work (accessed 15/1/22).

9. By happy coincidence, Ravilious shared his birthday with Cartier-Bresson, as he also did with Archie Parkhouse, a Dolton farmer, friend and neighbour who featured in many of his finest images.

10. The Beaford Old Archive images can be accessed at https://beafordoldarchive.org.uk/index.php (accessed 15/1/22).

11. More than 600 of George Tucker’s own portfolio of documentary photographs (including many of the small North Devon town of Hatherleigh) can now be viewed on www.georgetucker.co.uk (accessed 15/1/22).

12. Chapman’s Wild Goose and Riddon (2000) is a landmark publication of his Dartmoor photographs. A further selection can be viewed at www.chrischapmanphotography.com (accessed 15/1/22). He contributed the Foreword to Ravilious’s A Corner of England (1995) and created, with Ravilious, a joint touring exhibition to mark the Year of the Photographer in 1998. Their photographs were also shown side-by-side in the touring exhibition that Farms for City Children commissioned in 2006 to mark the thirtieth anniversary of that charity’s establishment at Nethercott House near Iddesleigh in North Devon. Chapman is one of the contemporary Devon artists who were featured in the millennial volume of the Association’s Transactions. (Pery, 2000)

13. John Lane (1930-2012) also served as a trustee of the Dartington Hall Trust for many years and was instrumental in the foundation of Schumacher College at Dartington. His books included an encomium for the county of Devon (Lane, 1998) and an affectionate study of Devon churches, richly illustrated by the photographs of Harland Walshaw (Lane and Walshaw, 2007). He also contributed a reflection on Devon to the millennial issue of the Association’s Transactions. (Lane, 2000)

14. Ravilious’s Beaford Archive photographs have been acquired by a number of other galleries and organisations. Over 160 are listed on the website of the Museum of Barnstaple and North Devon, which also organises a documentary photography competition inspired by his work. See https://ehive.com/objects?accountId=4559&query=Ravilious+ (accessed 15/1/22). With the support of the South Western Arts Association and Sotheby’s, 24 exhibition prints were presented to the North Devon District Hospital in the 1980s, when the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital acquired a further set. More recently the Victoria & Albert Museum in London acquired 20 prints which are listed on its website at

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/search/?q=Ravilious,%20James&page=1&page_size=15 (accessed 15/1/22).

15. The National Sound Archive recordings of Hamilton and Ravilious in conversation can be accessed at http://cadensa.bl.uk/uhtbin/cgisirsi/?ps=trvyfGlqms/WORKS-FILE/257980076/9 (accessed 15/1/22).

16. The Beaford New Archive can be accessed at https://beafordarchive.org (accessed 15/1/22). In 2015 the original negatives of the New Archive photographs were transferred for safe-keeping to the South West Heritage Trust’s Devon Heritage Centre in Exeter. Beaford’s curation of the Archive is guided by its Archive Steering Group of external experts who offer advice to its Trustees.

17. As noted above, the recording of oral histories had been included in the original concept for the Beaford Archive. The social historian, E. W. Martin, began work on recording reminiscences of local people for Beaford in 1973 with the aid of a grant from the Nuffield Foundation. Eight years earlier he had published an account of life in Okehampton (Martin, 1965) and twenty-seven years later he contributed a reflection on rural Devon to the Association’s millennial issue of its Transactions. (Martin, 2000)

18. Another set of personal responses to Ravilious’s photographs has recently been published by the Royal Photographic Society. (Wright, 2021) The legacy of Ravilious’s photographs is also being promoted through a Twitter account bearing his name, @JamesRavilious. Some publications featuring Ravilious’s photographs are now out of print but they are often available for loan from Devon’s excellent public libraries, now operated by the charity, Libraries Unlimited.

References

Anon. 2016. Museums and Photography, Burlington Magazine 158, 1357.

Batten, J. 1989. A Selection of Work by James Ravilious (Royal Photographic Society, Bath).

Beacham, P. 2000. Down the Deep Lanes (Devon Books, Tiverton).

Burnard, R. 1890–4. Dartmoor Pictorial Records, Vols I–IV (published privately, Plymouth).

Chapman, C. 2000. Wild Goose and Riddon: The Dartmoor Photographs of Chris Chapman (Halsgrove, Tiverton).

Clair, J. 1998. Henri Cartier-Bresson Europeans (Thames and Hudson, London).

Common Ground 2000. The Common Ground Book of Orchards: Community, Conservation and Culture (Common Ground, Bridport).

Cox, P. 2005. The Arts at Dartington: a personal account 1940–1983 (Dartington)

Deakins, R. 2021. Byways (Damiani, Bologna).

Derounian, J., Smith, C. and Chapman, C. 1988. Changing Devon (Stabb House, Padstow).

Edgcombe, D. 2021. Tides of Change A lens on the North Devon Coast (Beaford, South Molton).

Gilpin, R. and Gilpin, M. (eds) 2008. The Pilgrim’s guide to Devon’s Churches (Cloister Books, Exeter).

Greeves T. 2012. William Pengelly’s Torquay The Photographic Record c 1860–1875. Rep. Trans Devon. Assoc. Advmt Sci.,144, 87–118.

Greeves, T. 2015. Dartmoor’s Earliest Photographs: Landscape and Place 1860–1880 (Twelveheads Press, Truro).

Greeves T. 2018. William Spreat (1816–1897): Photography of the Devon Landscape 1857–1866. Rep. Trans Devon. Assoc. Advmt Sci.,150, 223–54.

Hamilton, P. 1998. An English Eye – The Photographs of James Ravilious (Devon Books, Tiverton).

Harris, H. 2004. A Handbook of Devon Parishes (Halsgrove, Tiverton).

Hatt, M. 2017. The Recent Past – James Ravilious (Wilmington Square Books, London).

Hurley, D. 2016. Presidential Symposium April 2016 Science meets Art Aspects of 175 Years of Photography in Devon. DA News, Autumn 2016, 5–7.

Kember, J., Plunkett, J. and Sullivan, J. (eds) 2016. Popular Exhibitions, Science and Showmanship, 1840–1910 (Routledge, Abingdon).

Lane, J. 1972. Planning for Art (paper presented to the Town and Country Planning Association’s 1972 Conference on Planning and the Countryside).

Lane, J. 1998. In praise of Devon: a guide to its people, places and character (Green Books, Dartington).

Lane, J. 2000. Devon Lost … Devon Gained. Rep. Trans Devon. Assoc. Advmt Sci., 132, 275–98.

Lane, J. and Walshaw, H. 2007. Devon’s churches a celebration (Green Books, Dartington).

Martin, E.W. 1965. The Shearers and the Shorn: A Study of Life in a Devon Community. (Routledge and Kegan Paul, London).

Martin, E.W. 2000. Rural Society in Devon in the Twentieth Century: The Fate of the Rural Tradition. Rep. Trans Devon. Assoc. Advmt Sci., 132, 233–48.

Pery, J. 2000. The Visionary Gleam: Contemporary Artists and the Devon Landscape. Rep. Trans Devon. Assoc. Advmt Sci.,132, 193–232.

Ravilious, J. 1995. A Corner of England (Devon Books with The Lutterworth Press, Tiverton).

Ravilious J. and Ravilious R., 1980. The Heart of the Country (Scolar Press, London).

Ravilious, R. 2017. James Ravilious A Life (Wilmington Square Books, London).

Robinson, C.E. 1896. A Photographic Survey of Devon. Rep. Trans Devon. Assoc. Advmt Sci., 28, 313–5.

Timms, S. 2000. ‘Hoping for Entire Completeness’: The Pursuit of Devon’s Past. Rep. Trans Devon. Assoc. Advmt Sci., 132, 117–60.

Westcott, R. 2021. The Signpost. http://www.richardwestcottspoetry.com/2021/06/the-signpost.html (accessed 15/1/22).

Williams, W. 1963. A West Country Village Ashworthy Family, Kin and Land (Routledge and Kegan Paul, London).

Wright, I, 2021. Ravilious on Ravilious. The Decisive Moment (Quarterly Journal of the Documentary Group of the Royal Photographic Society) 23, 8–23.