Reflections on 7 photographs

Viewers respond to looking at a photograph in many different ways. So, there is little to be gained through trying to generalise on what a particular image means or seeks to convey. This paper concludes by presenting a small sample of Ravilious’s photographs, accompanied by the author’s personal reflections upon them. Hopefully this will encourage readers to explore their own responses to these images and to the many others that they can discover on the Beaford Archive website and in available publications.18

Fig. 1 Gateposts 1981 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

A Trinity of gateway, tree and church stands silent against a solid sky. To gaze across to St Mary’s Church in the parish of Ashbury, is to take your eye into deepest Devon. This is one of the smallest, remotest of Devon’s 422 parishes (Harris, 2004) – no village centre (population of only 35 in the mid-twentieth century), no ‘big house’ (demolished the 1930s), and no casual passers-by (this is not on the road to anywhere else).

The few visitors who find their way to Ashbury mostly come and go cocooned in the comfort of their cars. But, if you make the journey on foot using public transport, you can garner a far deeper feel for the rhythms of life and the lie of landscape that give this area of Devon countryside its special character. An eighty-minute bus ride from Exeter will take you only as far as Castle Cross where you alight high on the crest of Broadbury, an exposed ridge running across North-West Devon. You then embark on a two-mile wander along quiet Devon lanes. Remembering to turn right at Bogtown, you at last find yourself standing where Ravilious stood in 1981. What inspired him to come this way, you wonder.

Today the gateway has been widened, the tree rises still magnificent against the sky and the church is closed. Officially at least. It no longer features in the Church of England’s listing of its 618 places of worship in Devon (Gilpin and Gilpin, 2008). At the time of Ravilious’s visit farm animals roamed the churchyard and St Mary’s was about to be formally declared redundant. But not unloved. Wonderfully, the door still opens thanks to the church being cared for by a family that holds its ancient roots in Ashbury. Inside you come as close to stillness as you can anywhere in this transitory world. And someone has pinned up on the wall their own poem inspired by once looking at this photograph.

Fig.2 Olive Bennett with her Red Devon Cows, Cupper’s Piece 1979 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

Many of Ravilious’s most striking photographs open our eyes to the close relationship between farmers and the animals in their care. This is one of his best-known and most reproduced images. It featured in the Leica Gallery’s 2000 exhibition in New York City (and, as a result, in the pages of The New Yorker magazine), the Victoria & Albert Museum acquired it for its permanent collections, it helped inspire the BBC’s 2007 film of Ravilious’s work and in 2021 it fronted the Burton’s publicity for its An English Eye exhibition in Bideford. It is a picture that has attracted a range of different responses from viewers.

Olive Bennett and her prize-winning Red Devons used to be a familiar sight to travellers as they crossed Beaford Moor on their way to and from Great Torrington. A detailed 1963 study of rural life in North Devon found that local people referred to four different types of farmers – ‘real farmers’, ‘good young farmers’, ‘dog and stick farmers’ (those who did little work themselves and liked to think they were gentlemen farmers) and ‘Up Country Johnnies’ (people who had moved in from outside the Westcountry). (Williams, 1963, 14) Ravilious always photographed for real and this image reminds us that not all real farmers are men.

Fig.3 Running for the school bus 1982 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

This is an image that never stays still. The boy will always be running despite the nearby road sign’s warning ‘Slow’ and the headstones’ promise of eternal rest. There are reminders here of the maxim attributed to a medieval German theologian: ‘There is no stopping place in this life – nor is there ever one for any person’. To those who know the photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson (an inspiring hero for Ravilious), there is a distant echo of his split-second image, taken fifty years earlier, of a be-hatted gentleman striding over a Paris puddle on his way to who knows where. (Clair, 1998, 23)

Ravilious never cropped his photographs and this one demonstrates his fine sense for composition as well as his skill in ‘catching the moment’. He took it from the tower of St Mary’s Church in the North Devon village of Atherington. Health and Safety restrictions have reduced opportunities today to climb the stairs in our medieval church towers. But if you ever get the chance, do take it. You never can be sure what you will see as you look down on our world from above.

Fig.4 The BBC Computer, Primary School Open Day 1985 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

Ravilious had an eye for what was becoming new in village life as well as for old ways that were at risk of disappearing. We so take computers for granted today that it has become hard to appreciate or recall the amazement – and sometimes bafflement – that their arrival in people’s daily lives brought. Here the generations come together as Mrs Agate and Dolton Primary School children tentatively explore the wonders of the modern machine.

As Robin Ravilious has pointed out, there is a nice comparison to be made between this photograph and one of the old Dolton pictures loaned by a local resident for copying into the Beaford ‘Old Archive’. Dating back to the first decade of the twentieth century, that image recorded an inquisitive group of villagers gazing at the first car, a Wolseley, to be owned by a Dolton resident – the local doctor, Dr Alexander Drummond (1856-1908). The first arrival of the car, as later that of the computer, marked a real turning point in rural lives in terms of communication with the ‘outside world’.

Fig.5 Barnstaple Pannier Market 1979 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

Market day has long been the traditional highpoint of the farming week in North Devon. Go back sixty or seventy years and some farming families never travelled further than their local market town except on special occasions. The North Devon towns of Barnstaple, Bideford, Great Torrington and South Molton retain their grand market halls although open-air cattle markets in their town centres have gone.

Barnstaple’s splendid Pannier Market, built in 1855, still plays a key part in the social and commercial life of the town. Fashions – both in people’s clothes and also in the types of food and other goods on sale – have changed since Ravilious took this photograph on a crowded market day forty-three years ago. The author’s mother, growing up during the First World War on her family’s small farm at Swimbridge, retained vivid memories of taking eggs to sell at Barnstaple Pannier Market during that war – and seeing the crowd turn blacker month by month as more families went into mourning for their menfolk lost on the battlefield.

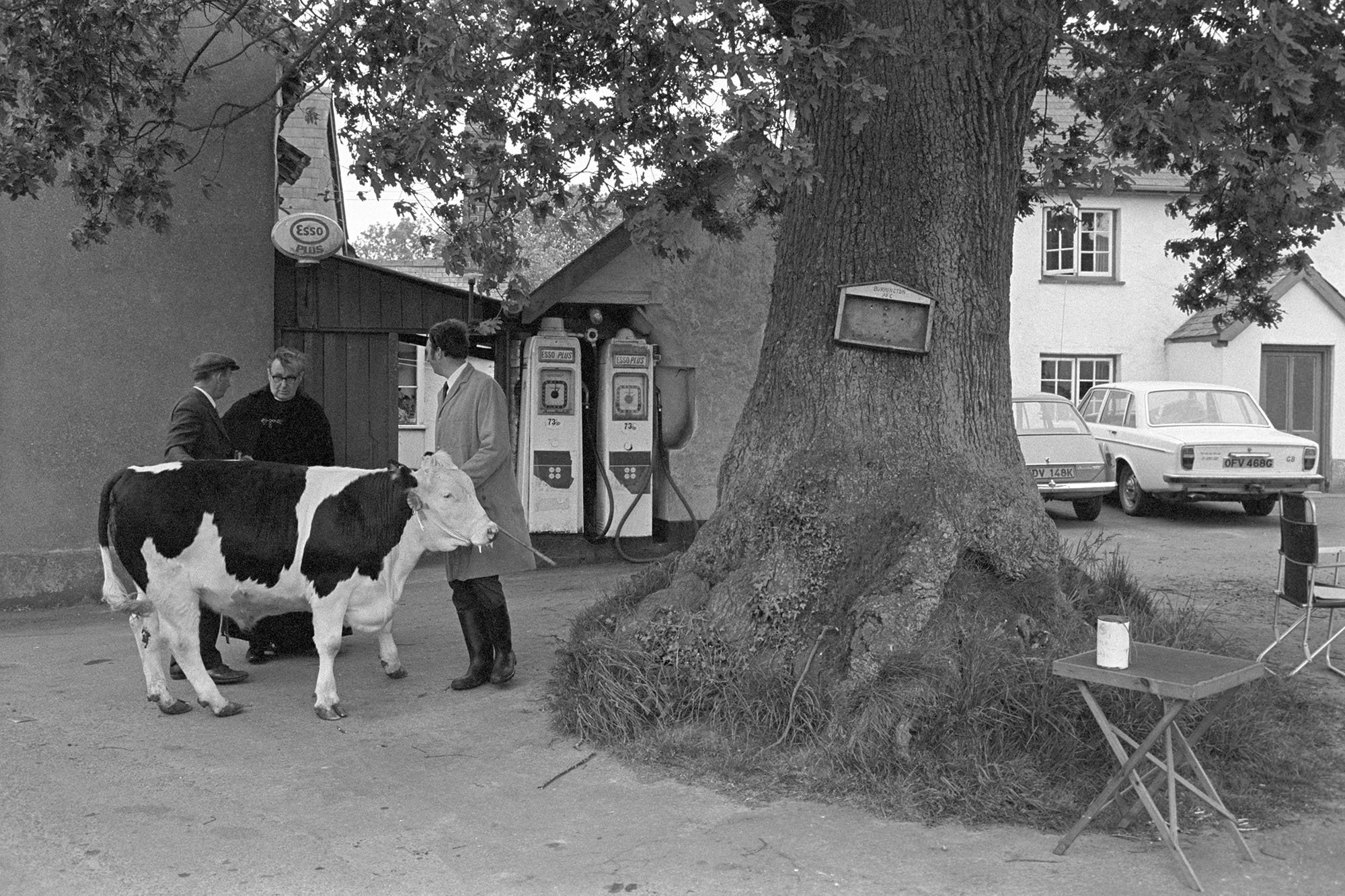

Fig. 6 Reverend Richards and prize bullock beneath the village oak 1975 (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

Ravilious never artificially created scenes for his photographs but sometimes one of them can seem so replete with artfully spaced detail that it reminds you of a stage set. Shakespeare’s line that “All the World’s a Stage” could apply to this image very well, with the ‘players’ being the tree, the folding table, the pumps and the cars as well as the parson and the farmers with their prize-winning, rosetted bullock. The ‘village tree’ still remains a prominent feature in the centre of a good number of Devon villages but its function as a community noticeboard has faded. In this photograph the village football team’s noticeboard, neatly aligned to the lean of the Burrington Oak, hangs empty – pending the start of the new season perhaps.

It used to be said that the essentials for a village’s well-being were the five Ps – Primary School, Public Transport, Post Office, Parish Parson and Petrol Pump. (Derounian et al., 1988, 1) Burrington, like so many other North Devon villages, has seen these ‘essentials’ fall away one by one. Its annual Trinity Monday Sheep and Cattle Fair, the event that set the scene for this photograph, came to an end in 1993.

Fig.7 Chawleigh Week Cross 1988. (Copyright: Beaford Archive)

Ravilious had great enthusiasm for ‘laning’ – the art of exploring country lanes and opening your eyes to whatever you happen to encounter. Here he has paused beneath one of Devon’s many thousands of rural signposts. Presiding over its crossroads as a silent sentinel of place, it stands ever ready to guide the wayward traveller and to offer passers-by some sense of certainty.

Its four arms, with their gracefully curving supports, raise questions for the traveller. Who was it who first measured the way to Barnstaple so carefully to be sure that it was eighteen and a quarter miles and not just a plain eighteen (or eighteen and a half)? What obstacles lie in wait for the incautious motorist tempted to take the shorter route to Chulmleigh? And what ever will you find when you get to ‘Sth Molton Rd’?

The image brings to mind a conversation the photographer Chris Chapman had nearly fifty years ago when he was travelling Dartmoor in the company of his donkey, Mistletoe. A local resident, who had worked for forty-eight years as a milkman living deep in the moor near Princetown, told him:

‘One day a chap came ‘ere and said “Ernie, you’ve seen nothing of the world, stuck out ‘ere all your life!” I told him straight, “I’m just like a signpost. I may not be going anywhere but I can tell you a lot about where you’re going!”’ (Chapman, 2000, 127)

Back in the 1980s the local council clearly felt it important to keep Chawleigh Week Cross well-posted. It presents a different, decaying picture to the passer-by in these days of SatNav and Google Maps. (Westcott, 2021)