Our Future

Andy Bell, Director of North Devon Biosphere Reserve shares his thoughts on how these photographs by James Ravilious and Roger Deakins reflect the Biosphere’s considerations for our future.

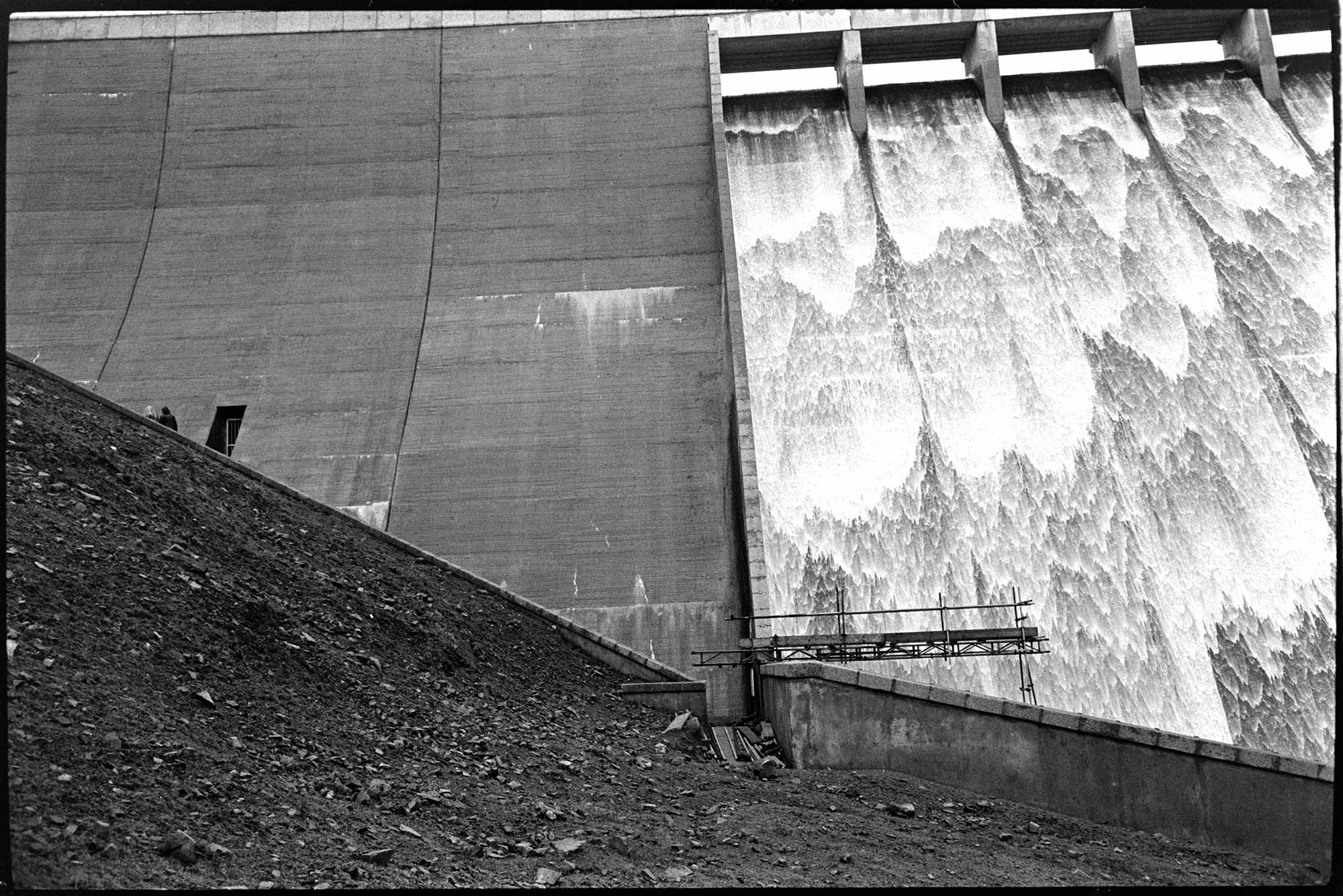

‘A key question for us is: how can we ensure that we continue to have enough water resources for consumption in the future? We’re working with partners to store water in the peat on the moor so that it is actually cleaner by the time it comes down to the reservoir. This means there’s less energy and effort going into cleaning the water itself, so it saves cost. It also results in less sediment going into the reservoirs, extending their life and minimising the number of reservoirs we have to build.’

Water cascading over reservoir wall, Meldon. Documentary photograph by James Ravilious for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts

Northam rubbish dump, Northam Burrows, Westwood Ho! August, 1973. Documentary photograph James Ravilious for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts

‘Northam Burrows has a landfill site that is positioned at the end of the spit. The spit has been there in various guises for thousands of years, but it has never really been the same shape.

Now we know that the Pebble Ridge is moving due to sea level rise and a reduction in the supply of pebbles from the coast, so we’ve got to work out what we’re going to do with the landfill. We’ve been doing work to model how it’s going to change over the next 100 years and to identify the most cost-effective way of dealing with it.

One option is to re-excavate the landfill site, which no-one can currently fund. The other extreme would be to accept we have to defend the site ad infinitum. That means putting a wall around it which is also an expensive option, especially if you have to keep maintaining it in the future. So the median option to defend it for now, but over the next 50 years to think about how the waste could be extracted and re-used, leaving the site with no risk. So we’re banking on new technology in the future which will recover the waste and use it, and using lower cost options to defend it in the interim. We’re not planning to contain it forever as it’s not viable. It’s about how we manage the risk.’

‘Technology and education have completely changed. Some of the jobs today’s children will do in 50 years time haven't even been invented yet, so we have to think about what our society will look like for the generations ahead and build creativity into education so it can respond to future changes. It’s important to link people to nature, but at the same time we need to embrace a bolder future.

We’ve been exploring the use of sensors that will make us aware of where the ecosystem is doing well and where it’s going wrong so that we can have a rapid response to fix any problems quickly. An array of sensors on water quality, air quality and biodiversity proxies would be an interesting way of helping people become more aware of their environment.

Then you have new technologies that promote “farming by the inch”, and driverless vehicles to manage woodlands. What will be the impact of that? The number of people actually linked to the land is dwindling and will reduce further. Against the background of our remoteness from the land, how can we counter that to make people still feel part of the environment and appreciate the benefits we get from it? How can we stop the land feeling like it’s something ‘out there’ and a stranger to them?’

School children using computer BBC Micro, Dolton, June 1984. Documentary photograph by James Ravilious for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts

Woman in phone box, talking on phone, Dolton, January, 1979. Documentary photograph by James Ravilious for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts

‘We’re now a very connected society, which can be a double-edged sword. It’s great to be connected with other communities, but the problem with over-connection is that we can lose our distinctiveness and become more homogenised.

As one of 669 Biosphere Reserves across the world, we aim to embrace the common approaches of how we work together but at the same time recognise our distinctiveness. Our twin biosphere is in Kenya, and we have many problems in common, such as rural poverty and resource use. Often the solutions are similar but they apply at different scales, and it’s good to share that knowledge and understanding and to share and celebrate our designation as a network.

What makes the North Devon Biosphere Reserve distinctive - and what marks us out as one of the most progressive - is that we don’t deal primarily with biodiversity. We’re looking at people in the environment and using different tools to try and address things in a far more integrated way to secure a better future by linking people and nature. We’re trying to build up biodiversity through development and economic activity, and working with them rather than always coming up against them.’

‘Appledore has an amazing knack for building very big ships in a very small yard, and the naval architects have a huge amount of skill which has been of influence internationally.

Now the shipyard struggles economically, and we have to think about how we can adapt and use those skills and marine technologies. We have a big blue space out there which is important, not just for giving us fish but for climate regulation and modification generally. We can work with the marine area to adapt and use those skills in new ways that are environmentally benign’

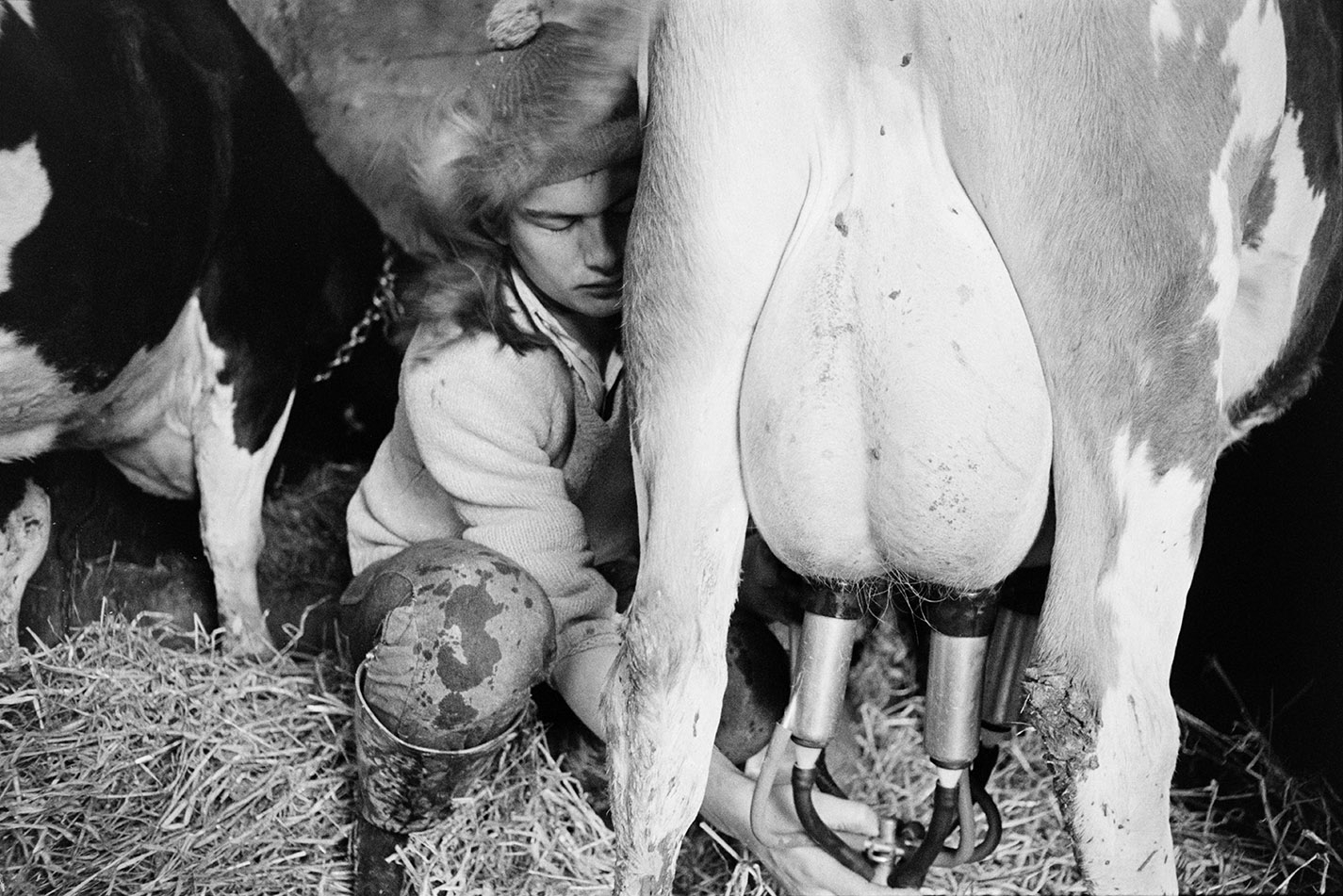

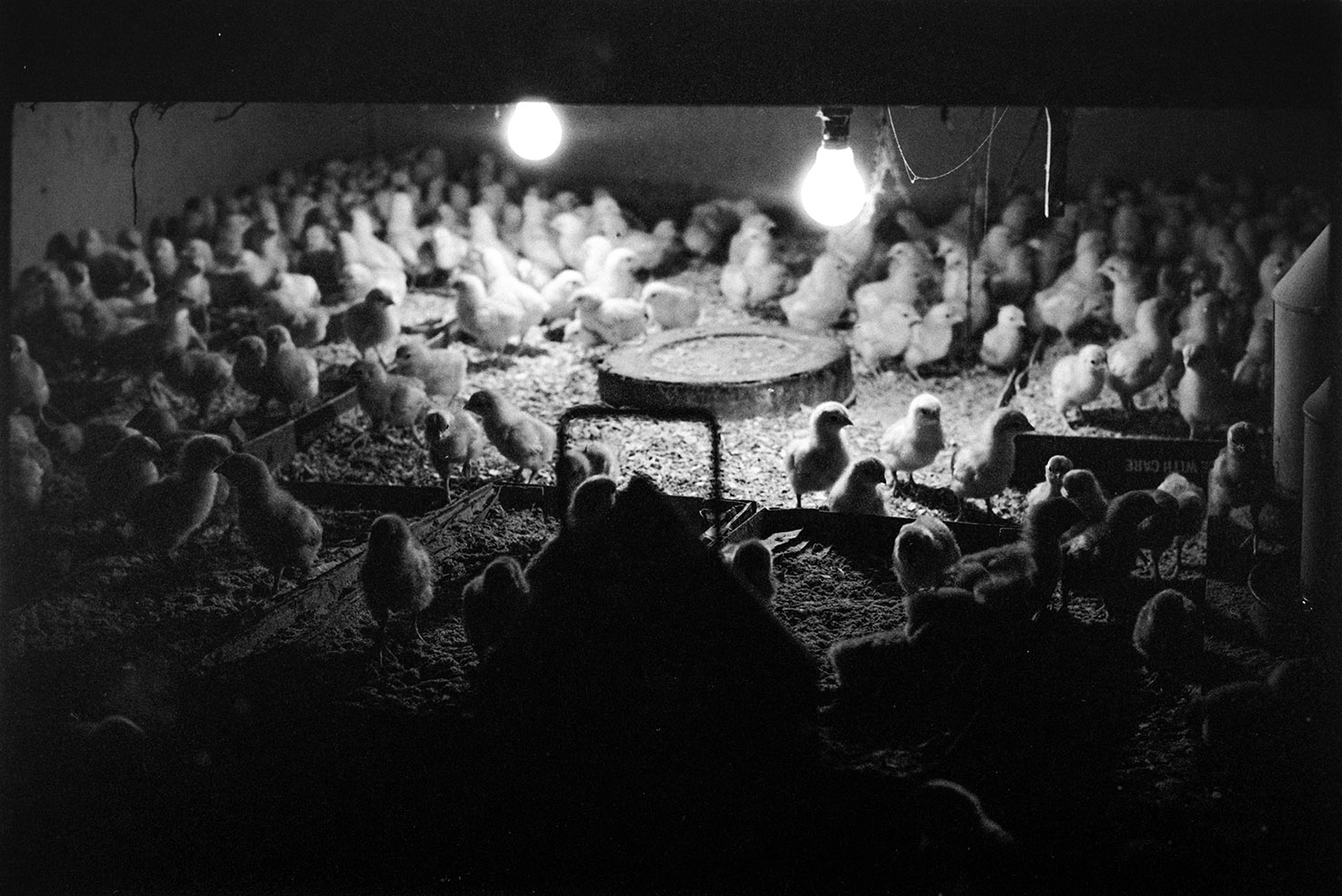

Documentary photograph by James Ravilious for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts

Documentary photograph by James Ravilious for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts

‘Dolton Beacon Garage is an important focal point for many things. If it weren't there, people would have to go another 10-15 miles to get petrol, which might have lead to the demise of the villages because they would get their service from that more distant location.

Dolton Beacon is an important place to come and get the energy for their cars, but is that energy right in the long term? If we move to hydrogen cell fuel technology, will it be a hydrogen station in the future?

There’s a broader question about energy in our rural villages. How will it be used and distributed? What will be its effect on communities? If you don’t have to go to a garage to get fuel and you can charge up your vehicle at home, will that make villages more resilient? While you fill up at home, you can do your shopping locally! Whatever happens, our reliance on the use of energy, its form and its distribution will shape the way our communities are sustained in the future.’

Flooded landscape, February, 1974. Documentary photograph by James Ravilious for the Beaford Archive © Beaford Arts

‘Flooding has always been with us, but the signs are that it’s getting worse as we have more intense winter storms and drier summers. In terms of the Biosphere Reserve’s future, we need to influence the number of times an area floods by changing the way that the land is managed and used. For the last 8 - 9 years we’ve been working with farmers to improve the permeability of the soils, and by trying to increase the amount of rough grassland and planting more trees to intercept the flow.

We’re also trying to help the communities that do get flooded become more resilient, and we’re collaborating with councils to ensure that any new developments don’t exacerbate the problem. Fortunately, the councils are embracing the development of ecosystem services which will be developed into a land use policy for the area’.