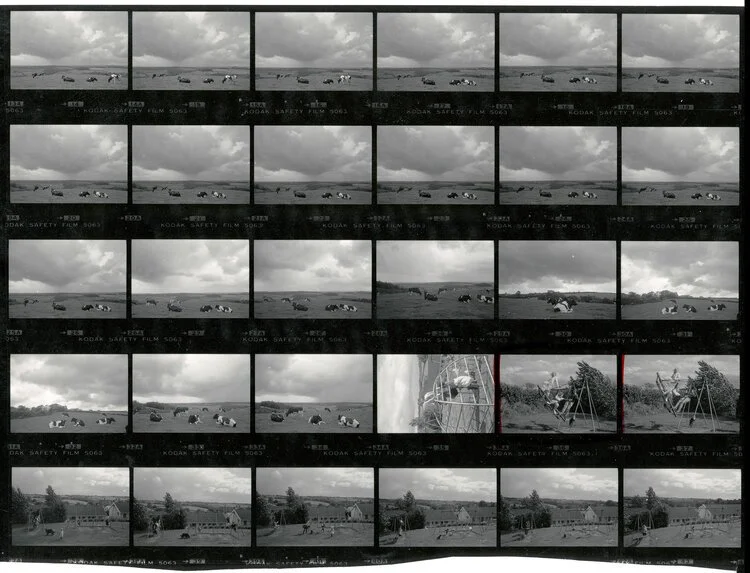

James Ravilious

James Ravilious

Photo by James Ravilious

Photo by James Ravilious

My happiest memories of Greenwarren House date from the 1980s, when James remained a fully committed member of the Centre, devoted not only to his own work, but to all that Beaford sought to do, his generosity to his colleagues and readiness to take part in whatever was going on seeming to be of the very essence of the place. His wife Robin supported his commitment not only through her hard-working but gracious presence on open days and other special occasions, but also with her own informed artistic judgment as and when called for. Both enjoyed remarkable artistic heritages, James being the son of Eric Ravilious, the war artist, wood engraver and designer, and Tirzah Garwood, also an artist and wood-engraver, while Robin was the daughter of the glass-engraver Sir Laurence Whistler and the actress Jill Furse, granddaughter of the poet Sir Henry Newbolt and distantly related to the painter Sir Joshua Reynolds. Robin was, moreover, a niece of the painter and designer Rex Whistler.

Robin’s mother died shortly following her birth, while her uncle Rex lost his life in action in Normandy in 1944. Eric Ravilious died in Iceland in 1942, having opted to accompany a crew from RAF Kaldadarnes searching for a missing aircraft, but on a plane that itself failed to return. Tirzah Garwood passed away from cancer in 1951, when James was twelve. James and I formed a bond through having both served under the headmastership of William Brown, I at Ely and James at Bedford. His mother had apparently hoped that James would go to Bryanston, which would surely have been far better suited to his temperament, but he spoke quite warmly of Brown, despite finding life in a conventional public school of that time less than agreeable. Through Stephen Odom, a master at Bedford who had been a chorister at St. John’s College Cambridge during my time in the choir, I was able after James’s death to draw his old school’s attention to the work of its notable alumnus, and an exhibition of James’s work followed.

There were fault lines underlying Beaford’s relationship with James traceable to the time of his original employment by John Lane. No time limit was set for his engagement as an artist in residence; little if any thought was given to how the post would be funded in the longer term; and a condition was imposed that the copyright in James’s photographs for the Beaford Archive would be owned by the Centre after his death. I became involved in the negotiation of successive revisions of the agreement covering James’s own work (as distinct from the material he collected for the so-called “Old Archive”), both with James himself and with Robin after his death.

In his highly self-critical way, James categorized his “Oeuvre” into best, good and other work, and ground rules were set regarding its reproduction, dissemination and exploitation. I was concerned that, in consultation with the Centre, James and his family should be free to benefit from the work through their own initiatives; the one concession I deemed it impossible for a charity to make was as to the ultimate ownership of the copyright, galling though this surely was for James and Robin. I was also determined to promote dialogue, particularly following James’s death in 1999, and thereafter chaired a steering committee of nominees of both the Centre and Robin for well over a decade, stepping down only when new arrangements acceptable to Robin were put in place following the successful Heritage Lottery Fund bid made under Mark Wallace’s leadership.

The Heart of the Country, a book featuring James’s photographs with text by Robin, was published in 1980. With the help of Emma Nicholson and her husband Sir Michael Caine (the businessman, not the actor), Diana Johnson and I made efforts (albeit unsuccessfully) to raise money to restore the ancient barns in the Greenwarren House gardens to create a permanent home and visitor centre for the Beaford Archive. A team of staff and volunteers was formed to curate both the old and new images and things seemed to be going in a positive direction, but then the clouds began to gather.

On advice from our mutual friend Tony Foster, then SWA’s visual arts officer, James had already opted to work half-time, with a view to developing his work beyond the confines of his Beaford brief. Indeed, before the end of the 1980s, he was making noises about the possibility of severing the “umbilical cord” with Beaford altogether. Eventually, in 1990, after 17 years, he decided to take “a year off”, explaining in a letter to me that his body was having trouble reacting to darkroom chemicals. This was surely a symptom of the problems with lymphoma with which he was hospitalised for a time three years later and which would cause his death before the end of the decade.

However, further work for Beaford was thwarted by the inability of Bob Butler to establish an effective working relationship with James, who wrote to me in May 1993, saying ”I’m afraid I just cannot bring myself to cooperate with Bob.” The latter unquestionably admired James’s work, but simply could not find the means within himself to cope with James the person, whether as an individual or an artist. For me, James was truly a friend, so of course I was ready whenever needed to meet and talk things through, and we frequently exchanged letters or faxes. From 1996, for example, I find the following from James, with which handwritten copies of Edward Thomas’s poems Adlestrop and Thaw were enclosed:

Thank you very much for all your time - & a wonderful lunch … Talking to you is always a great help – though I wish we had even more time for music, art – & cheese!

Yet, hard as I tried, with Bob as well as with James, I could not contrive a solution and the arrival of Jennie Hayes in 1998 proved all too late.

After reading Robin’s biography of James (James Ravilious; a Life, 2017), I came to appreciate how, from the very beginning, James and Robin’s personal circumstances had been so exceedingly modest and that, besides feelings of being marginalised and undervalued, serious financial hardship had a bearing on James’s complaints during the last years of his life. I wrote to Robin, saying how I wished that, despite all my conversations and correspondence with James, I had understood enough to seek to alleviate his situation in practical terms. She replied that the “if only syndrome” was something she also felt, regretting that she had lacked the confidence she now had to stand up for James and promote his work as she had learnt to do.

In any event, it was lamentable that Beaford, having facilitated much of James’s work for so long, should have laid itself open to such criticism at the end. Peter Hamilton’s obituary in The Independent was far from complimentary and I then had the uncomfortable experience at James’s memorial service in Chulmleigh (20th March 2000) of speaking immediately following a tirade against Beaford by the painter Robert Organ (although he has long since become a good friend). The greatest sadness is that, within the final year or two of his life, James’s work was at last beginning to receive broader public recognition. The revelatory retrospective exhibition An English Eye at the Royal Photographic Society in Bath in 1997 was followed a year later by the publication of Peter Hamilton’s book of the same name, featuring James’s photographs with a foreword by Alan Bennett.

James’s own contribution to the Beaford Archive was described by Barry Lane, then Secretary-General of the Royal Photographic Society, as “a unique body of work, unparalleled at least in this country for its scale and quality.” It has since been the subject of further publications and exhibitions and, as a result of the HLF funding, been given greatly extended exposure through digitisation. As I write, an exhibition of James’s work is about to open at The Foster Art & Wilderness Foundation in Palo Alto, California, Tony Foster and James having as young men traced together the footsteps of Robert Louis Stevenson in his Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes. All we lack is James himself, an outstanding artist and a most lovable man.

(Since I wrote my original memoir, the RPS exhibition has found a permanent and appropriate home at the Burton Art Gallery in Bideford, while James’s life and work are now recognised by a blue plaque on the family home in Chulmleigh).

Photo by James Ravilious

Photo by James Ravilious