Conception

Dartington Hall. Photo by Josh Pratt, courtesy Dartington Trust

The Plough Arts Centre, Great Torrington

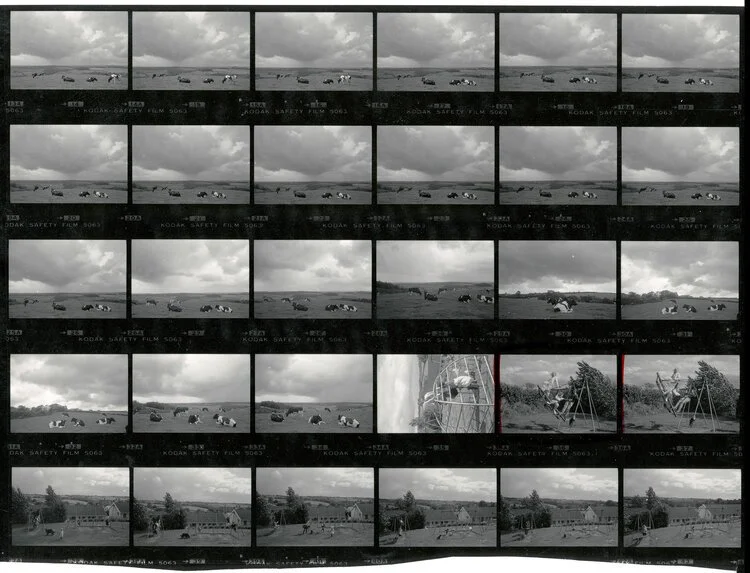

Photo by James Ravilious

In the mid-1960s, rural North Devon remained a relatively remote part of the country, the link road from the M5 to Barnstaple being still a thing of the future. The Dartington Hall Trustees took it into their heads to attempt to replicate in the region some of the regenerative initiatives the Elmhirsts had inspired in South Devon some forty years earlier. With the guidance of the designer Frank Thrower, they engaged sixteen glass blowers from Sweden to form the core of a glassmaking business in Great Torrington and to impart their skills to local people.

But, in the Dartington tradition, a job was not enough and the Trustees wished at the same time to establish an arts centre in the area. They found a large house with substantial grounds in the nearby village of Beaford and proceeded to recruit John Lane as its founding director. Both he and his wife Truda had been art students at the Slade and, with a teaching diploma from London University’s Institute of Education, John had worked both in schools and at Bretton Hall College of Education in Yorkshire. Harland Walshaw, a subsequent director at Beaford, told me what an unorthodox and inspiring teacher John had been at his school.

The Beaford Arts Centre opened at Greenwarren House in 1966, but John had the vision to conceive that, in an area with poor infrastructure and communications, what was needed in the main was not a centre to which people would travel, but rather a hub from which events and activities could radiate into the towns and villages round about. In so doing, he set a pattern for rural arts centres up and down the land. John would have it that:

It began with a whimper: there was a house … but little else: no chairs, no desk, not a telephone, even a typewriter.

Be that as it may, he in no time organised a festival featuring more than thirty events all over North Devon tailored to a wide variety of tastes. Early adherents also recall with affection concerts in the house itself and craft classes in the outbuildings.

A large property needed a purpose greater than simply housing administrative offices and the occasional event and, in association with Devon County Council’s education department, Greenwarren House became a base for residential courses for schoolchildren, the row of small wellington boots in the entrance hall becoming a much-loved feature of the place. In 1969, John founded Orchard Theatre, a touring repertory theatre company with Andy Noble as its first artistic director. Two years later, he instigated a photographic project to record a traditional way of rural life that was already beginning to disappear. For the first year, he engaged a young photographer, Roger Deakins, who would go on to become an Oscar-winning cinematographer and attain a knighthood. The project was then taken on by James Ravilious, who over the next 17 years was to create almost 80,000 negatives, mainly of the world between the rivers Taw and Torridge, and also start collecting an “old archive” drawn from the albums of local people, which now comprises some 7,000 images dating mostly from 1880-1930.

John Lane was also instrumental with others in establishing the Plough Arts Centre in the former drill hall in Torrington, a separate, building-based venture to be managed separately, but in cooperation with Beaford.

Glass blowers at Dartington Crystal

Photo by James Ravilious

Greenwarren House, Beaford

Photo by James Ravilious

Poster from arts festival, 1968

Incorporation

Beaford was initially run as a department of the Dartington Hall Trust, but in 1980, while I was engaged in incorporating the Trust itself, I was asked to form a separate charitable company to take on the control and management of Beaford, albeit with continuing financial support from Dartington. Thus began my association with Beaford, which was to continue directly for more than twenty years and indirectly until the present day.

John Lane had been appointed a trustee at Dartington in 1974, but then assumed the chair of Beaford’s steering committee and so became the first chairman of the new company. I must have joined the Beaford board at an early stage, for I was appointed its vice-chair in December 1984. John then persuaded me to take on the chairmanship in May 1987. This, I was to come to realise, was to permit him, while remaining on the board, to have greater freedom to criticise the work of his successors as director. John and I were to remain friends right up until the time of his death in 2012, but he stayed on the Beaford board until 1997 and it was almost inevitable that we would find ourselves increasingly at variance, given the essential need for me as chairman to support and defend each director in office, unless and until I had genuinely good reason to do otherwise.

Management

My initial involvement in Beaford’s management began with a financial crisis, for John Lane’s former pupil and later assistant at Beaford, Harland Walshaw, had for the past two or three years run an exciting programme, but at an unsustainable cost. Solvency was regained only through the sale of the house originally built by the Dartington Hall Trustees for John Lane and his family and latterly used as an annexe for the residential courses.

For a year or so, the helm was temporarily taken by a locally-based poet, travel writer and playwright, Paul Hyland. In his gentle, pipe-smoking manner, he would continue to support Beaford’s work for the best part of a decade and was a good friend to me. Together with others, we were involved in appointing a new director, Diana Johnson, an Oxford music graduate who during her first marriage had worked in arts administration in Australia. Thus began an enduring friendship that was enhanced by Diana’s second marriage to John de la Cour, then music officer for the regional arts association, South West Arts.

Until concluded towards the end of the decade by an extended period of maternity leave accompanying the arrival of Diana and John’s son Elmley, her reign at Beaford was characterized by a distinctive fusion of competence and élan. She related well to Paul Chamberlain and his successor Nigel Bryant as artistic directors of Orchard Theatre, as well as to James Ravilious and his wife Robin. The well-established programme of events in local towns and villages, the theatre company’s tours and the continued development of the photographic archive were supplemented by a succession of special projects. One involved a residency by an ensemble led by the celebrated clarinettist Alan Hacker culminating in young people having their GCSE music compositions professionally performed in Crediton parish church. Of another, involving performances and workshops by the Alberni String Quartet, the distinguished critic David Cairns wrote in The Sunday Times that, along with Open Chamber Music at Prussia Cove, it was

as significant for the long-term health and vitality of our musical existence as anything I have encountered in the more celebrated centres.

But these projects were by no means confined to classical music, for a residency by Lanzel African Arts featured North Devon’s first Yam Festival.

Beaford came to national prominence when The Observer published an article critical of the views and policies of the arts minister, Richard Luce, a piece based in large part upon interviews with staff at Greenwarren House concerned with the difficulty for rural projects remote from the centres of commerce to supplement public subsidy with business sponsorship. To his credit, the minister went out of his way to understand the situation better by talking directly with Diana and her colleagues, which led to his expressing praise for Beaford’s work in both the House and the press. Subsequently, in a letter he wrote to me in July 1990, he added a handscript note to the effect that:

I am a great admirer of the Beaford Centre and all that you achieve.

In 1987, Beaford’s 21st anniversary, HRH Prince Edward had come to visit, so these were good years for Beaford and, while the fact that the books balanced may have caused John Lane to question whether still more might have been ventured, it was a great comfort to me, so that Diana and I worked together with much harmony.

Following the interregnum resulting from Diana’s lengthy time away on maternity leave, when Paul Hyland again came to the rescue, Bob Butler was appointed director in mid-1990. He immediately put Beaford firmly back on the map in the public’s mind by staging a North Devon Festival upon the lines of the one with which John Lane had originally launched the Centre. I opened the whole venture in Victoria Park, Bideford, with the local MP Emma Nicholson, who wrote to me afterwards with thanks for

a splendid afternoon. The parachute jump was spot on time … I was glad of the opportunity to be with you.

Bob Butler’s personality was very different from Diana’s: there was much energy, but also rough edges; he attracted great loyalty from some, but rooted antipathy from others, as will become apparent. However, it should be borne in mind that his family life was darkened as the decade progressed by the breast cancer from which his wife Wendy eventually died in 1999. Be all that as it may, Bob and I became good friends and remained so until his death a few years ago from a rare form of cancer. He felt at home with what he called my “remote control” form of chairmanship, an inevitability given the international nature of my professional life. However, there was in fact an inexorable proliferation of committee work and I came to spend increasing amounts of time travelling to and from North Devon, a 60-mile round trip at a minimum.

Bob deserves credit for three principal achievements during more than seven years at Beaford. Firstly, he negotiated a secure, air-conditioned home for the negatives of the photographic archive in the North Devon Record Office in Barnstaple. He then responded with great purpose to an appeal from Torridge District Council and other people for Beaford to take under its wing the Plough Arts Centre in Torrington, which was at imminent risk of closure. This was a major undertaking, with far-reaching financial implications as well as the difficulties inherent in managing a split-site organisation, our astute vice-chairman during this period, Prebendary Anthony Geering, reminding us how the children of Israel came to grief when they ceased being nomads and took to building the Tower of Babel. Finally, Bob worked tirelessly on a bid to the National Lottery Fund, which yielded sufficient funds not only for substantial refurbishment of the facilities at Greenwarren House, but also for major improvements and extensions at the Plough.

Jennie Hayes, a photographer by background, succeeded Bob in the spring of 1998. By this time, the challenge of funding all that Beaford was doing had become acute, the volume of work and level of staffing having increased markedly over the past few years, but at a time when public funding levels from the local and district authorities as well as South West Arts were in steady decline. Jennie focused our minds on the need for Beaford to equip itself for survival well into the new millennium. To this end, it was necessary to revisit its primary purpose. A consultant, Adrian Watts, was engaged to guide the process and, following extensive internal discussions and consultation with the funding bodies, a series of public meetings was arranged.

The principal conclusions were that (i) through Beaford’s efforts over the past few years, the Plough was now strong enough take back its independence; (ii) running children’s courses had never been core to Beaford’s role, but rather an expedient to ensure that Greenwarren House was fully used; and (iii) if Beaford could reduce its fixed costs, it would gain the flexibility to adapt its arts activities to changing rural and cultural conditions and respond to, influence and benefit from new opportunities for funding and creative partnerships. Greenwarren House and its grounds were thus to be sold and a modest office base found from which a team of peripatetic arts workers would operate throughout the North Devon region. In so doing, an endowment fund would be created to underpin the organisation’s long-term survival.

It was a radical solution, but undoubtedly timely. I had hoped all along that Jennie would remain in post to manage the transition, but she was determined to make way for a new director. For me, after almost a decade and a half in the chair, it was certainly time to go, although (as will be seen) I was to play a lasting role in the support of Beaford. I was touched to receive a letter from Nick Capaldi, the chief executive of South West Arts and future head of the Welsh Arts Council, to the effect that:

We have certainly shared some moments of high drama. But even when the latter have appeared to be at their most challenging, I have always valued your quiet authority and wisdom. I shall miss this hugely.

Sad to say, it took Beaford the best part of another fifteen years to implement the new plan in full. The grounds to the rear of the house were sold for the development of executive dwellings, but Greenwarren House itself was retained and the children’s courses continued. The fact was that, for more than thirty years, these courses had never been adequately financed by the local education authority and a large part of the proceeds from the sale of the gardens was absorbed in trying out a variety of further means to render them economic. Meanwhile, for a few years, directors and board members came and went and considerable instability ensued until Mark Wallace was appointed director at the beginning of 2007. Over time, he has more than realised the vision for a mobile, flexible and clearly focused arts team responsive to the changing world around it and, despite repeated attempts to secure the children’s courses on a sustainable footing, eventually accepted the need to leave Greenwarren House behind. The organisation, with an office base in South Molton, is now back in good heart and well regarded locally, regionally and indeed nationally.

Orchard Theatre

The original Orchard Theatre Company members including the first Artistic Director Andy Noble (bottom right)

Entertaining crowds on Westward Ho! beach. Photographer unknown.

John Lane founded the Orchard as a touring repertory company, its debut performance having been Harold Brighouse’s Hobson’s Choice in Torrington Town Hall. It became a familiar and valued feature of the regional arts network and, in the later 1970s, I would take my children to the annual pantomime in Barnstaple’s Queens Hall (now upgraded as the Queens Theatre). From the outset, staffing was on equity terms.

By the time I became directly involved in the 1980s, the Orchard remained part of Beaford, but operated from separate premises in Newport Road, Barnstaple, and had its own steering committee, which was normally convened on the morning of the days when Beaford’s main board met in the afternoon. Under the artistic direction of Paul Chamberlain, who departed in 1982 for Theatr Clwyd in Mold, and then of Nigel Bryant, the company was exercising a three-year franchise for South West Arts as the region’s major touring theatre company. But there were new trends in theatre being pioneered in the South West, first by Footsbarn (founded in 1971) and later by Kneehigh (dating from 1980), which sought to move away from text-bound work, whether established or newly commissioned, to the creation of vigorous, popular theatre for a broad spectrum of audiences in a variety of locations with multi-facetted forces.

The Orchard’s pre-eminence as a regional touring company first faced serious threat when its franchise came up for review in 1985. Criticism of standards and quality were strongly rebutted, but, with the benefit of hindsight, one can see that this was camouflage for growing questions as to the value of the repertory model as compared with the lively new forms now coming on stream. A succession of assessment and appraisal exercises followed over several years, during which the Orchard under Nigel Bryant was continuing to commission new plays, increasing its audience numbers and achieving plaudits for tours on a national scale. However, nothing could disguise the fact that there were fundamental differences of conviction between those who regarded Orchard as offering middle-of-the-road repertory and sought a new approach and Nigel himself, who stood firmly resistant to change.

In 1989, Nigel left Devon to work for the BBC at Pebble Mill and was replaced by Bill Buffery from the Royal Shakespeare Company and National Youth Theatre. Both Bill and I became extensively involved in correspondence and meetings about South West Arts’ latest appraisal, with which, despite material reservations, we sought to cooperate. However, Bob Butler’s appointment at much the same time brought new perspectives to bear on the situation, given his past experience in administrative roles with both Kneehigh and the Colway Theatre Trust’s community plays. For so long as the Orchard remained integral to Beaford, why should its policies not be more closely aligned with those of the parent organisation? Moreover, following the absorption of the Plough, could cohesion within the whole organisation not be best served by relinquishing the Orchard’s Barnstaple base and moving its headquarters to the Plough in Torrington?

I myself was attracted by this scenario, and it would not have excluded the subsequent disposal of the Beaford site and the acquisition of additional office space in Torrington. But it was not to be, for the Orchard clung to its effective independence, a determination heightened by the poor chemistry between Bob Butler and Bill Buffery. In 1997, the Orchard finally lost its SWA funding subject to some modest transitional support, and expressed the wish to continue on a reduced scale as a separate charitable entity. There followed the rather grisly business of dividing up the assets, Orchard Theatre taking all the theatre equipment and a share of reserves, but not the freehold property in Newport Road, with which (as will be seen) Beaford had only recently been endowed and with the capital value of which I was determined it should not part. Orchard Theatre closed in 2000.

Bill Buffery went on to set up a new company, Multi Story Theatre, with Gill Nathanson, long-term Orchard Theatre company member and Education Officer, and they remain active in North Devon and far beyond. Moreover, through the dauntless leadership of Richard Wolfenden-Brown and much community effort and enthusiasm, the Plough continues with a modicum of outside funding to provide a lively programme of exhibitions, film and live events. Change is invariably an opportunity as well as a threat and Beaford could surely not have been transformed with the success Mark Wallace has now achieved if it were still attempting to manage a theatre company and a fixed venue on the side.

Poster from Orchard’s first show in 1969

Orchard News - Live Theatre Threat

Bill Buffery & Gill Nathanson performing Beauty & the Beast - a recent Beaford commission in partnership with Multi Story Theatre

Photo by Peter Buffery

James Ravilious

James Ravilious

Photo by James Ravilious

Photo by James Ravilious

My happiest memories of Greenwarren House date from the 1980s, when James remained a fully committed member of the Centre, devoted not only to his own work, but to all that Beaford sought to do, his generosity to his colleagues and readiness to take part in whatever was going on seeming to be of the very essence of the place. His wife Robin supported his commitment not only through her hard-working but gracious presence on open days and other special occasions, but also with her own informed artistic judgment as and when called for. Both enjoyed remarkable artistic heritages, James being the son of Eric Ravilious, the war artist, wood engraver and designer, and Tirzah Garwood, also an artist and wood-engraver, while Robin was the daughter of the glass-engraver Sir Laurence Whistler and the actress Jill Furse, granddaughter of the poet Sir Henry Newbolt and distantly related to the painter Sir Joshua Reynolds. Robin was, moreover, a niece of the painter and designer Rex Whistler.

Robin’s mother died shortly following her birth, while her uncle Rex lost his life in action in Normandy in 1944. Eric Ravilious died in Iceland in 1942, having opted to accompany a crew from RAF Kaldadarnes searching for a missing aircraft, but on a plane that itself failed to return. Tirzah Garwood passed away from cancer in 1951, when James was twelve. James and I formed a bond through having both served under the headmastership of William Brown, I at Ely and James at Bedford. His mother had apparently hoped that James would go to Bryanston, which would surely have been far better suited to his temperament, but he spoke quite warmly of Brown, despite finding life in a conventional public school of that time less than agreeable. Through Stephen Odom, a master at Bedford who had been a chorister at St. John’s College Cambridge during my time in the choir, I was able after James’s death to draw his old school’s attention to the work of its notable alumnus, and an exhibition of James’s work followed.

There were fault lines underlying Beaford’s relationship with James traceable to the time of his original employment by John Lane. No time limit was set for his engagement as an artist in residence; little if any thought was given to how the post would be funded in the longer term; and a condition was imposed that the copyright in James’s photographs for the Beaford Archive would be owned by the Centre after his death. I became involved in the negotiation of successive revisions of the agreement covering James’s own work (as distinct from the material he collected for the so-called “Old Archive”), both with James himself and with Robin after his death.

In his highly self-critical way, James categorized his “Oeuvre” into best, good and other work, and ground rules were set regarding its reproduction, dissemination and exploitation. I was concerned that, in consultation with the Centre, James and his family should be free to benefit from the work through their own initiatives; the one concession I deemed it impossible for a charity to make was as to the ultimate ownership of the copyright, galling though this surely was for James and Robin. I was also determined to promote dialogue, particularly following James’s death in 1999, and thereafter chaired a steering committee of nominees of both the Centre and Robin for well over a decade, stepping down only when new arrangements acceptable to Robin were put in place following the successful Heritage Lottery Fund bid made under Mark Wallace’s leadership.

The Heart of the Country, a book featuring James’s photographs with text by Robin, was published in 1980. With the help of Emma Nicholson and her husband Sir Michael Caine (the businessman, not the actor), Diana Johnson and I made efforts (albeit unsuccessfully) to raise money to restore the ancient barns in the Greenwarren House gardens to create a permanent home and visitor centre for the Beaford Archive. A team of staff and volunteers was formed to curate both the old and new images and things seemed to be going in a positive direction, but then the clouds began to gather.

On advice from our mutual friend Tony Foster, then SWA’s visual arts officer, James had already opted to work half-time, with a view to developing his work beyond the confines of his Beaford brief. Indeed, before the end of the 1980s, he was making noises about the possibility of severing the “umbilical cord” with Beaford altogether. Eventually, in 1990, after 17 years, he decided to take “a year off”, explaining in a letter to me that his body was having trouble reacting to darkroom chemicals. This was surely a symptom of the problems with lymphoma with which he was hospitalised for a time three years later and which would cause his death before the end of the decade.

However, further work for Beaford was thwarted by the inability of Bob Butler to establish an effective working relationship with James, who wrote to me in May 1993, saying ”I’m afraid I just cannot bring myself to cooperate with Bob.” The latter unquestionably admired James’s work, but simply could not find the means within himself to cope with James the person, whether as an individual or an artist. For me, James was truly a friend, so of course I was ready whenever needed to meet and talk things through, and we frequently exchanged letters or faxes. From 1996, for example, I find the following from James, with which handwritten copies of Edward Thomas’s poems Adlestrop and Thaw were enclosed:

Thank you very much for all your time - & a wonderful lunch … Talking to you is always a great help – though I wish we had even more time for music, art – & cheese!

Yet, hard as I tried, with Bob as well as with James, I could not contrive a solution and the arrival of Jennie Hayes in 1998 proved all too late.

After reading Robin’s biography of James (James Ravilious; a Life, 2017), I came to appreciate how, from the very beginning, James and Robin’s personal circumstances had been so exceedingly modest and that, besides feelings of being marginalised and undervalued, serious financial hardship had a bearing on James’s complaints during the last years of his life. I wrote to Robin, saying how I wished that, despite all my conversations and correspondence with James, I had understood enough to seek to alleviate his situation in practical terms. She replied that the “if only syndrome” was something she also felt, regretting that she had lacked the confidence she now had to stand up for James and promote his work as she had learnt to do.

In any event, it was lamentable that Beaford, having facilitated much of James’s work for so long, should have laid itself open to such criticism at the end. Peter Hamilton’s obituary in The Independent was far from complimentary and I then had the uncomfortable experience at James’s memorial service in Chulmleigh (20th March 2000) of speaking immediately following a tirade against Beaford by the painter Robert Organ (although he has long since become a good friend). The greatest sadness is that, within the final year or two of his life, James’s work was at last beginning to receive broader public recognition. The revelatory retrospective exhibition An English Eye at the Royal Photographic Society in Bath in 1997 was followed a year later by the publication of Peter Hamilton’s book of the same name, featuring James’s photographs with a foreword by Alan Bennett.

James’s own contribution to the Beaford Archive was described by Barry Lane, then Secretary-General of the Royal Photographic Society, as “a unique body of work, unparalleled at least in this country for its scale and quality.” It has since been the subject of further publications and exhibitions and, as a result of the HLF funding, been given greatly extended exposure through digitisation. As I write, an exhibition of James’s work is about to open at The Foster Art & Wilderness Foundation in Palo Alto, California, Tony Foster and James having as young men traced together the footsteps of Robert Louis Stevenson in his Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes. All we lack is James himself, an outstanding artist and a most lovable man.

(Since I wrote my original memoir, the RPS exhibition has found a permanent and appropriate home at the Burton Art Gallery in Bideford, while James’s life and work are now recognised by a blue plaque on the family home in Chulmleigh).

Photo by James Ravilious

Photo by James Ravilious

North Devon Trust & Foundation

In or around 1980, at the behest of Michael Young, the sociologist and social and political activist ennobled in 1978 as Baron Young of Dartington, the Dartington Hall Trustees decided to extend their commitment to the north of the county by establishing the Dartington North Devon Trust. As it turned out, this was to involve little more than employing a person, giving him with an office and a bit of support and leaving him to generate such additional projects as he felt able.

The first director, Dr. David Davies, was a man of both distinction and resource – a geophysicist who, after working as a seismologist in both Cambridge and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, had edited the journal Nature for several years before coming to Devon. His arrival coincided with the period during which the government through the Manpower Services Commission (MSC) was investing extensively in youth training schemes and, in no time, David set up a network of workshops throughout the region. As a capable amateur musician, he also made his presence felt on the local arts scene and became a valued member of the Beaford board. Sadly, he was all too soon attracted to move to Yorkshire for work with Michael Young on another of his projects.

His successor, Michael Gee, proved to be a thoughtful and cultivated person, but without David’s dynamism. With the closure of the MSC in 1988, youth training was no longer an option and the North Devon Trust came to initiate several disparate projects concerned with community mediation, saving Devon’s apple orchards, helping fund children’s music lessons and, for a time, maintaining an interpretation centre at the Braunton Burrows. For a year or two, Michael also organised a small arts festival in Lynton and Lynmouth.

Quite early on, John Lane had replaced Michael Young as chairman of the North Devon Trust. No doubt frustrated by the conditions attaching to public funding and the necessity for ambitions to be tailored and trimmed to the ever-changing pattern of Arts Council and other external policies, he presented a paper to the Beaford board in March 1988 that advocated seeking an endowment to make the Centre self-sufficient and thus permit it to adopt whatever policies it chose in a completely free and independent manner. This was surely a dream of Utopia and events were to prove that, even after it had the benefit of significant endowment, Beaford would continue to rely substantially upon public, charitable and commercial funding for both its core and project costs

Much to his credit, however, John took the opportunity of the sale by Dartington of the Torrington glassworks to make the case to his fellow trustees for an endowment fund to be set aside for North Devon. But he also saw it as a chance to enforce a merger between Beaford and the North Devon Trust and this, much to John’s irritation, I felt strongly obliged to resist. Besides the fact that an arts centre was an inappropriate home for some of the Trust’s disparate range of projects, the salary of the director was markedly out of kilter with pay levels affordable in the arts sector. However, Diana Johnson worked with Michael Gee on a paper exploring ways in which the two organisations might cooperate and I, albeit reluctantly, agreed to accept the additional burden of joining the board of the North Devon Trust.

Thus it was that, at the end of 1991, the Dartington North Devon Foundation was established with an endowment of £500,000 for the support of Beaford and the North Devon Trust. A stipulation was attached that the Foundation should for an initial period of at least five years maintain the grants previously made by Dartington to Beaford (£25,000) and the Trust (£35,000), although Diana and Michael had estimated that at least £800,000 would be required for this purpose. However, I had in the course of the negotiations secured the major concession that the freeholds of Greenwarren House and Orchard Theatre’s premises in Barnstaple should be assigned to Beaford.

The first trustees of the Foundation were to be John Lane for the Trust and myself for Beaford, with an independent chairman in the person of John West, formerly regional director of Barclays Bank, who on retirement had joined the team of Dartington’s own merchant bank, Dartington & Co.

In practice, Beaford and the North Devon Trust were to find little common ground. I had been told by John Lane that the Trust’s future policy would be focused on rural change, but no rationalisation of its disparate range of activities ensued, except that it managed with difficulty to relieve itself of the burden of running the centre at Braunton Burrows. The Foundation’s grant to the Trust was required to support the cost of the director and his establishment, so that it was impossible to contemplate reducing it without undermining the way the Trust was run. However, the policy of maintaining grants at their historical levels was steadily eroding the Foundation’s capital and a decision eventually had to be taken either to change the policy or to pay out the endowment until it was used up.

Around the time of the millennium, it was finally decided that the Foundation must cease further erosion of its capital and aim to stabilise it at a level of around £300,000. The unavoidable consequence was that the North Devon Trust would no longer be able to employ a professional staff, but have to operate on a voluntary basis. Given the implications of this decision for Michael Gee in particular, it was an intensely difficult one to take, hence the delay in facing up to it for so long. However, John West and I were fortunate that the North Devon Trust was now represented on the Foundation’s board by John Dare, a retired headteacher of a pragmatic frame of mind. After a period of transition, the Trust’s annual grant was reduced to £3,000 to cover the Trust’s central administrative expenses, the fact being that all of its remaining activities were essentially self-supporting. Beaford’s grant was also reduced, but only to £15,000 a year.

I replaced John West as chairman of the Foundation upon my retirement from the Beaford board, but John remained a trustee for another eight years and thereafter served as Honorary President until his death at a great age in 2014. His clarity of thought, breadth of knowledge and innate charm had been of inestimable value to the Foundation and a cause of pleasure for all involved. We had together started to broaden the membership of the board and, at the end of 2014, under the influence of further new recruits, the obvious conflict of interest borne by those Foundation trustees who were also trustees of Beaford or the North Devon Trust was finally addressed. The membership of the Foundation’s board was fundamentally changed accordingly. At the same time, there was serious debate as to whether, given its modest size, the Foundation still had a useful role to perform, or whether it would make better sense for its assets now to be dispersed amongst its two principal clients. The most cogent argument for the continued existence of the Foundation came from Mark Wallace at Beaford, who explained that core funding from any source besides Arts Council England was difficult if not impossible to secure and that it greatly strengthened Beaford’s stance vis-à-vis the Council if there was another body consistently willing to contribute to its core costs, and not simply to support specific projects.

There was also intense debate as to whether the Foundation was obliged indefinitely to continue to support both Beaford and the North Devon Trust, the outcome of which was that in future all grants from the Foundation were to be subject to a system of annual applications, with decisions to be made on the merits of each case. Beaford was at this point warned that its annual grant might need to be significantly reduced in the light of new applications from the Trust. However, when approached for proposals, the Trust’s response was to ask for half of the available money, so that it might then decide for itself what to do with it. This being unacceptable, we were requested to supplement the funds of the Trust’s Young Musicians Support project (YMS), but feared this would simply serve to disincentivise YMS’s long-established fundraising processes. For several years, we instead made modest investments in workshops for young musicians arranged by YMS with professional performers appearing in the region, but, hard as we tried, we could not elicit the kind of feedback required to assess the real impact of these events. Consequently, we recently engaged the services of a consultant to explore with the county music hub, YMS and other interested agencies whether the Foundation could serve as a catalyst for promoting cooperation between the various individual initiatives concerned with musicmaking among children and young people in North Devon, the hope being that the whole might prove greater than the sum of the parts. A five-year project to this end has since been commissioned.

Beaford suffered a rocky few years during the 00s, but under Mark Wallace has gone from strength to strength, enjoying a measure of security through its national portfolio status at Arts Council England and with a programme now extending beyond the arts to both heritage and environment. Indeed, I consider that, given the greatly enhanced condition and accessibility of the photographic archive and a partnership with the North Devon UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, Beaford has now addressed the subject of rural change as fully and effectively as John Lane could ever have expected from the North Devon Trust. However, the Trust for its part can celebrate in particular the extraordinary success of Orchards Live! in promoting the preservation and renewal of Devon’s apple orchards through courses, talks and other events, the dissemination of information via its website, the acquisition of equipment for members’ use and assistance with the marketing of produce. Michael Gee’s crucial contribution to this project has been crowned by his publication in 2018 of The Devon Orchards Book.

John Lane

Towards the end of his life, John suffered a catastrophic stroke, leaving him physically paralysed, but with his mind as active as ever, as I was to discover when visiting. Following his death in 2012, there was a major memorial gathering at Dartington, when much was said about his work down there, but it seemed to me that his seminal contribution to the cultural life of North Devon was being forgotten.

I wrote a piece for Beaford’s website, recording that his setting of a pattern for rural arts centres had been “a stroke of genius, conducted with imagination, energy and a sense of joy”. I then discussed with Truda, her sons and others close to John how his work at Beaford and thereabouts might best be celebrated. There followed several memorial events at the Plough, for which I was able to find some funding from the Foundation: a piano recital by Allan Schiller, whom early adherents remembered playing Schubert’s Wanderer-Fantasie long ago in Greenwarren House; a conversation between Satish Kumar and James Lovelock, which drew a packed house; an exhibition of John’s own paintings linked to a lecture on Samuel Palmer by Professor Sam Smiles; and a talk by Robin Ravilious about James’s work.

I believe justice was reasonably served in the end and cling firmly to the view that it is in North Devon and not Dartington where John’s true legacy lies.

Photo by James Ravilious